Distinguishing the Q-sectors

The need for dynamic alignment and synchronization – the capabilities associated with the top-Λ of the double-V cycle – arise as a consequence of the competitive pressures created by accelerating demand tempos. When looked at from the perspective of the economy as a whole, this leads to the Q-sectors becoming increasingly important in determining the nature of GDP growth. Instead of growth being defined solely in terms of the sales value of outputs of products and services, it becomes defined also in terms of increasing the use-value of those products and services in both B2B and B2C contexts-of-use (Hulten and Nakamura 2018). What makes the Q-sectors different, and how does that difference change the nature of the innovations needed to profit from providing services to the Q-sectors?

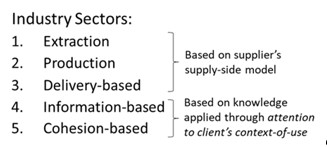

The economy is traditionally divided into three sectors: primary extraction, secondary production and tertiary services:

In 2021, the [primary] agriculture sector contributed around 0.96% to the USA Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In that same year, 17.88% came from [the secondary] industry, and the [tertiary] services sector contributed the most to the GDP, at 77.6%. Feb 8th, 2023

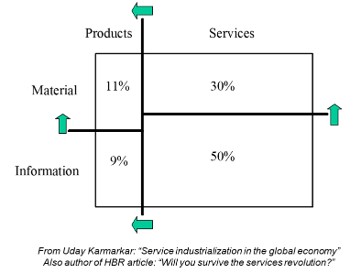

The services sector is thus nearly 80% of the economy, digitalization not only causing more and more of the economy based on secondary production to migrate into the tertiary sector (estimated at 30% in the figure below), but also causing more and more of the tertiary services sector to be information based (estimated at 50%).

In order to break down the tertiary services sector better, it is increasingly split into three sectors. The quaternary sector has come to be identified with information-based services, while the quinary sector is represented by the highest category of decision makers who formulate policy guidelines in Industry, Govt Departments, Science and Technology which have a profound impact on the economy. These latter two sectors have come to be referred to as the Q-sectors (Strukhoff 2016), leaving the remainder of the services sector to be distribution and delivery. There is however still not a widely shared definition of all five sectors, however, given the dependence of the quaternary and quinary sectors on postindustrial society (Kuzmin, Pyrog, and Melnik 2014). Of these, the most problematic to define is the quinary sector, described below as cohesion-based.

It makes sense to refer to the quaternary sector as information-based, where the value being created for the client is alignment to the client’s situation on the basis of the information necessary to doing this. Given the identification of the quinary sector with the formulating of policy by highest category of decision-maker, it makes sense that the value being demanded here is for the delivery of cohesion in the behaviors being expected to respond to those policy demands within the policy-maker’s context-of-use.

Distinguishing use-value from exchange value

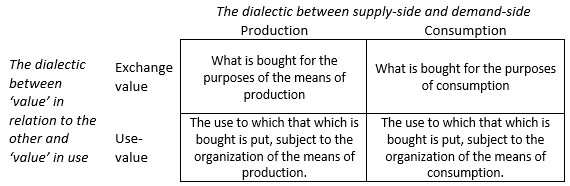

For this not to be an arbitrary choice of language, however, there has to be a structural basis on which to distinguish the Q-sectors, based on the nature of the demands being satisfied, as is the case for the first three sectors. This structural basis becomes apparent when we return to two dialectics originally defined by Marx, albeit requiring us to accept that Marx’s theory of value has been misinterpreted (Keen 1993a) based on Marx’s works having been read in terms of a labor theory of value (Keen 1993b). To establish a structural basis for distinguishing the Q-sectors (and to correct the misinterpretation of Marx), it is necessary to distinguish use-value clearly from exchange value at the same time as distinguishing the means of production from the means of consumption (Keen 1990). The two dialectics are

- Between use-value and exchange value, the exchange value being what is paid for a product or service as a ‘commodity’, while the use-value of what has been bought is the use to which it is put by its owner, whether as a business or as a citizen-individual.[1]

- Between production and consumption, where production, whether of a product or of a service, is defined by the organization of the means of production applied to what has been bought (which includes services, labor and materials); and consumption is defined as a citizen-individual’s organization of his or her means of consumption (which again includes services, labor and materials).

The difference between production and consumption, then, is whether the organization is of production for the purposes of securing a profit (aka surplus value) or of consumption for the purposes of the welfare and well-being of the individual in their praxis of living.[2] Putting these two dialectics together results in the following 2 x 2:

A number of conclusions may be derived from this:

- The primary task of the means of production in producing its outputs is defined by its organization.

- The profit (qua surplus value) is the difference between the exchange value of the outputs produced and the exchange value of the services, labor and materials used by the means of production.

- Labor is itself commoditized in the sense that its exchange value is determined by the way in which it is to be used within the context of a means of production or of consumption.

On the basis of this, we can make a distinction between the first three sectors and the last two Q-sectors:

- the profit derived from the first three sectors is derived from the way their outputs are used, whether by a means of production or of consumption; and

- the profit derived from the Q-sectors is derived from the effects of their services on the organization of either a means of production or of consumption, both of which are defined as contexts-of-use.

- Quaternary alignment reduces the costs of organizing the supply of labor, products or services necessary to a particular means of production or of consumption (as we see below in the relation of the bulk salt provider to the road traffic management system).

- Quinary cohesion reduces the costs of organizing the means of production or consumption per se (as we see below in the relation of Stockpile Reports to the way the bulk salt provider was able to run its business).

In understanding what might be driving innovation in the Q-sectors, therefore, we must focus on contexts-of-use, whether defined by the organization of a means of production or of a means of consumption.

Understanding Q-sector value in relation to value deficits

We have seen in Accelerating demand tempos and the double-V cycle how the use of drone technology and 3-D imaging software enabled Stockpile Reports to provide close-to-real-time data about the salt stockpiles of a bulk salt provider: this changed the way the bulk salt provider was itself organized. The bulk salt provider, supplying a number of different road traffic management systems regionally, could use this data to manage their logistics in such a way as to accelerate the tempo at which it could maintain continuity of supply under varying adverse weather conditions: this changed the way a road traffic management system could keep its bulk salt supply dynamically aligned with changing weather conditions. Stockpile Reports was profiting from the way it enabled the bulk salt provider to change the organization of its means of production through embedding a cohesive data management organization. The changed organization of the bulk salt provider was also able to profit from improving the way the road traffic management system could organize its means of production in the way it was able to make use of salt. For both Stockpile Reports and the bulk salt provider, a value deficit created by the current organization of their respective clients’ means of production could be reduced by changing that organization in such a way that their client could derive greater use-value from their means of production[3].

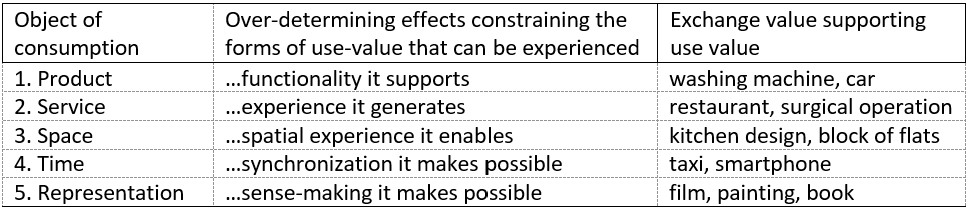

It is not so apparent what it might mean to profit from reducing the value deficit experienced by a citizen-individual in his or her pursuit of welfare and well-being within the context of his or her praxis of living. Consider, for example, the production of architectural ‘space’ by the means of production of the construction industry (Lefebvre 1991[1974]). This provides an opportunity to distinguish between a quantitative exchange value and the qualitative use-value experienced by the individual living in the space produced. Understanding the means of production in the terms proposed by Lefebvre allows us to consider a much wider range of ways in which supply-side commoditization of exchange-value (in the architect’s case a commissioned house) each with its way of supporting new forms of ‘use-value’:

The use-value of the first four of these types of object of consumption may be experienced ‘directly’, as for example in the 3rd type of “spatial practice” described by Lefebvre (Lefebvre 1991[1974]: p33) or in the effects on our lives of smartphones in the 4th type. The fifth, however, whether experienced as a work of art (representational space) or as the nature of (the design of) space itself (representations of space) over-determine the ways in which the citizen-individual frames demands themselves in relation to his or her experienced need.[4] The point, of course, is that the use-value being experienced is being experienced by the citizen-individual within the context of his or her praxis-of-living. Value deficit in this context refers to the individual’s experience of satisfaction engendered by the way s/he is organizing his or her context-of-use as a ‘means of consumption’.

Coming back to the question of innovation, then, we must consider not just supply-side innovations in how new services and products might be created that can acquire exchange value, but also demand-side innovations in how an individual might change the organization of his or her praxis-of-living itself. While we might consider the former to be about the business owner’s pursuit of profit, the latter has to be about the citizen-individual’s pursuit of satisfaction within the context of experienced value deficits.[5]

I will leave the dialectics between these two dynamics to the next post.

Notes

[1] The exchange value of labor depends on the way the market for labor has been organised. The payment that an individual receives for his or her labor then becomes that which s/he can spend on consumption. The use-value of that labor to the business owner depends on how its use is organized as part of a means of production. Whatever the citizen-individual spends his or her income on depends on the use to which s/he puts it as a part of his or her means of consumption, whatever s/he has to pay depending on the exchange value of the labor, goods or services bought.

[2] ‘praxis’ as in the exercise or practice of an art, science or skill in the way an individual takes up his or her life. See for example role as praxis. Having just finished grouting a very expensive glass mosaic backsplash as part of redesigning our kitchen, you will understand praxis-of-living in this context as the space within which I enjoy cooking!

[3] In practice, there is always a gap between the service made available to a client and the client’s particular needs – what we shall call a value deficit, the value being the value to the client of the services provided. ‘Value’ here is the way the client values the services provided, which may or may not be expressible in monetary terms. Value in these terms is therefore to be distinguished from the value to the service provider of the services provided. In the context of healthcare, see managing primary risk and the value deficit.

[4] The use-value of the fifth brings us to the way identifications shape the way we relate demand to experienced need and thus to the value deficits we experience as remaining. The importance of the fifth ‘representation’ is thus because of the way these identifications are themselves affected by the dynamics of Power/Knowledge (Foucault 1980) in determining how demand itself can be organized through, for example, the spatial structuring of a metropolis (Cunningham 2008). This is taken a step further by considering how the citizen-individual can be led to adopting (introjecting) narrative forms that shape what kinds of consequence s/he anticipates from different ways of organizing ‘truth’ (Massumi 2015).

[5] This raises the whole question of the relation between need, demand and desire – a question that brings us into the questioning of how we understand our human being.

References

Cunningham, David. 2008. ‘Spacing Abstraction: Capitalism, Law and Metropolis’, Griffith Law Review, 17: 454-69.

Foucault, M. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977 (The Harvester Press: Brighton, UK).

Hulten, Charles R., and Leonard I. Nakamura. 2018. “Accounting for Growth in the Age of the Internet: The Importance of Output-Saving Technical Change.” In. https://doi.org/10.21799/frbp.wp.2017.24: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Research.

Keen, Stephen. 1990. ‘Use, value and exchange: the misinterpretation of Marx’, University of New South Wales.

———. 1993a. ‘The Misinterpretation of Marx’s Theory of Value’, Journal of History of Economic Thought, 15: 282-300.

———. 1993b. ‘Use-value, Exchange-value and the demise of Marx’s Labor Theory of Value’, Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 15: 107-21.

Kuzmin, O., O. Pyrog, and L. Melnik. 2014. ‘Transformation of Development Model of National Economies at Conditions of Postindustrial Society’, Econtechmod – An International Quarterly Journal, 3: 41-45.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1991[1974]. The Production of Space (Blackwell Publishing).

Massumi, Brian. 2015. The Power at the End of the Economy (Duke University Press: Durham and London).

Strukhoff, Roger. 2016. “”Q Sectors”: Global Digital Transformation Leads to Economic Growth.” In Altoros. https://www.altoros.com/blog/software-dev-the-worlds-q-sectors/.