The last blog ended on the challenges faced by customers created by ‘market failures’. Market failure arises when providing a product or service to a market-defining aggregation of demand cannot be economically justified on the basis of capturing value from creating economies of scale or scope (Langlois 2003). This leads to the complexity issues that are not addressed by market offerings having to be picked up by customers within their own contexts-of-use. Over time, as market offerings become less and less effective in meeting the developing demands of a customers’ contexts-of-use, each customer’s environment becoming increasingly vortical (Baburoglu 1988) managing dynamic constraints imposed by suppliers in addition to those arising within their own situation.

The growth in the Q-sectors of the economy (Strukhoff 2016), i.e., the knowledge-based open K-type fourth and P-type fifth sectors[1], represents a response to this intensifying dynamic complexity. The associated growth in these Q-sector propositions is based on the provider being able to capture value from creating economies of alignment in addition to the economies of scale and scope already available to the market. These economies of alignment use digitalization to make dynamic orchestration and synchronization of operational capabilities economic, AI taking these economies even further.[2]

The state with its economy is a supersystem, its social organization defined in terms of how it justifies regulating the performance of corporations, including the corporations acting as instruments of government. Regardless of whether its government is democratically elected, the citizens of that state will be an ultimate source of selective pressures on the performance of the ecosystems within that state’s economy to the extent that they act as customers for its products and services.[3]

Given the presence of different kinds of exchange relation within the economy, therefore, there will need to be different kinds of governmentality through which the state can justify how it regulates different kinds of corporation (Boltanski and Thevenot 2006[1991]). These justifications will derive from the value to the economy of different kinds of relational contract necessary to each kind of exchange relation.[4] Each kind of justification will take the form of a different kinds of supracontractual norm,[5] each one having its way of regulating what corporations may expect from each other and what remains for customers to do for themselves. To understand what distinguishes the supracontractual norms regulating the Q-sector roles of corporations, we can examine the case of the English water industry.

Distinguishing the supracontractual norms for a Q-sector role

Consider the role of an English water utility in the lives of its customers. Here, the government’s privatization of the water industry in 1989 was to move it from being state controlled to having a ‘market’ relationship to its customers. This enabled the privatized industry to secure capital funding directly from capital markets based on the revenues its utilities could earn from their customers, removing the industry as a burden on the state’s general taxation.

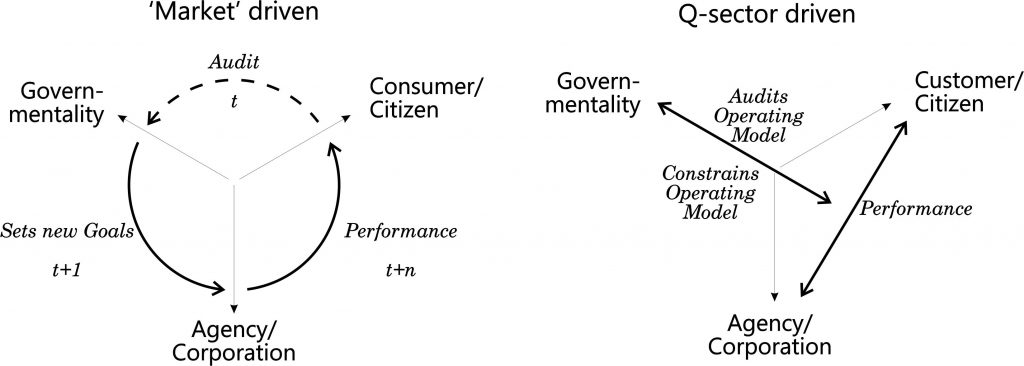

The success of this privatization was such that by 2022, more than 70% of the English water industry was in foreign ownership by investment firms, private equity, pension funds and businesses lodged in tax havens (Leach, Aguilar Garcia, and Laville 2022). Its regulation by Ofwat[6] was through a black-box model of operations constrained only by acceptable returns on capital to shareholders. It was ‘black-box’ because, provided that utilities met the requirements of its customers for consumable water within pricing constraints (the left-hand side of Figure 2), a utility could do what it wanted. The result was that “there [was] a much stronger focus on extracting revenue, rather than [on] the long-term health of a company” (Leach, Aguilar Garcia, and Laville 2022). The regulation of the water utilities remained focused on securing their financial resilience (Laville and Leach 2022), leaving the rest up to ‘market forces’.

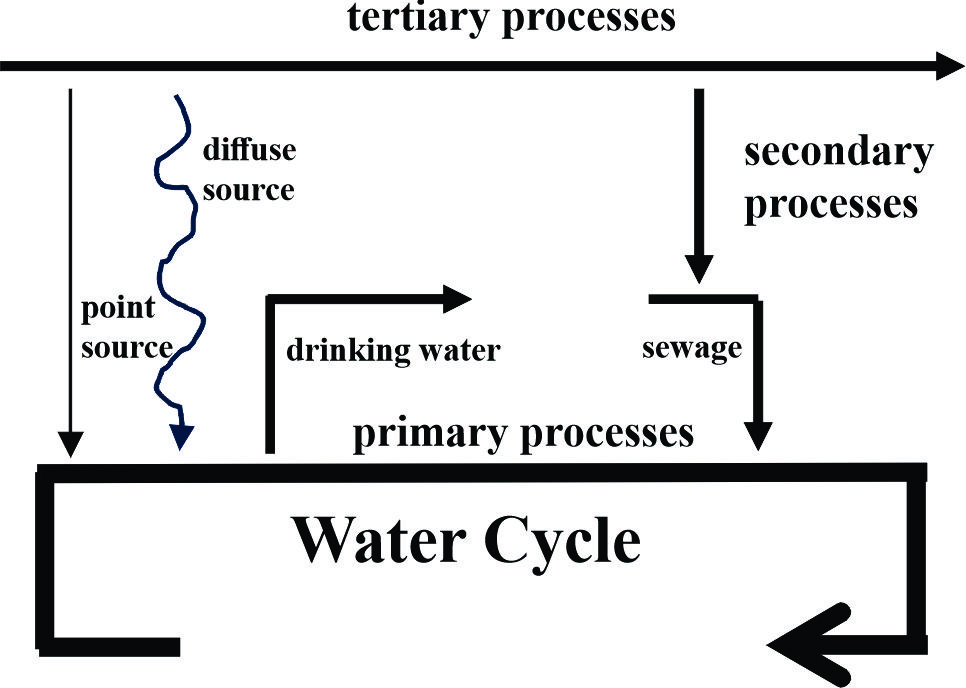

Figure 1: The processes impacting on the Water Cycle

The critique of this way of regulating is derived from the complexity of the context within which each utility works, subject to the varying dynamics of the water cycles in the catchments from which each one is serving its customers, dynamics which now have to include the effects of climate change. Figure 1 shows the complexity of this context in the relations to the water cycle of primary processes (‘input’ and ‘output’ processes to/from the utility’s customers), secondary processes (any process by which pollutants affect the primary process) and tertiary processes (any process creating the pollutants entering secondary processes). The critique is that while extensive investment went into the financial re-engineering of the industry (Leach et al. 2023), the particular issues associated with leakage and pollution have not been given priority (Laville 2023). Furthermore, the issues around the secondary and tertiary processes have remained unresolved by the government other than through the utilities being subject to investigation and fines from the English Environment Agency (Laville and Leach 2022).

For a utility to adopt a Q-sector role with its customers, its regulation would have to be based on a white-box model of the way it was behaving (right-hand side of Figure 2). This would require the transparency of a utility’s operating models and a commitment by the utility to a through-life duty of care to the well-being of its customers based on the use-value of its services to its customers. The focus would still be on providing consumable water within constraints, but effective performance would now be based on the sustainability of the operating model used by the utility to manage the interactions between its operating and capital expenditures within the context of its supply catchments and its customers’ use-characteristics.

Figure 2: The transition from a ‘market’ driven to a Q-sector driven approach to regulation

While a Q-sector supracontract would thus still include constraints on returns on capital[7], regulation would be on delivering Resource Adequacy with particular focus on efficiency, i.e., on the issue of leakages of all kinds, and on risk, i.e., on tolerance of shocks such as from drought and pollution.[8]

The basis of the different kinds of supracontract

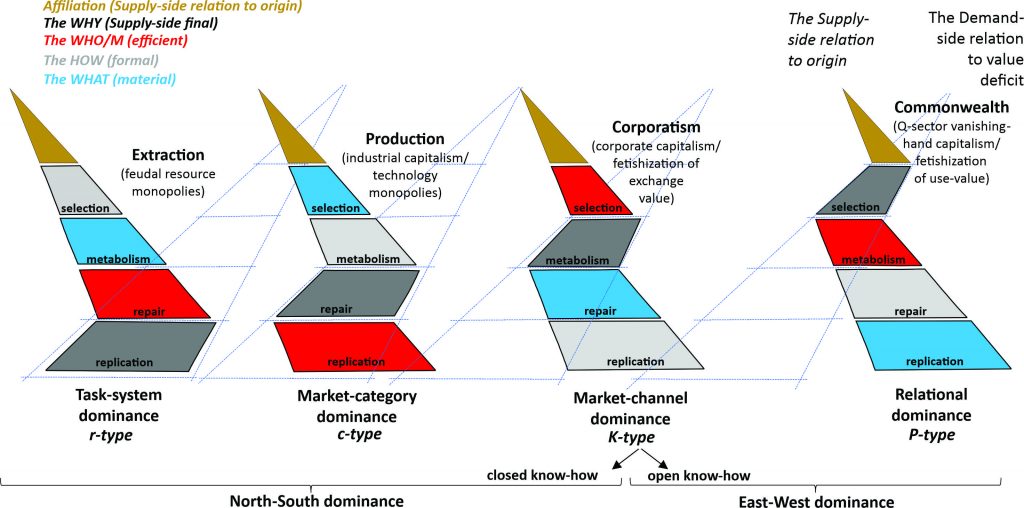

Figure 3 identifies the four different kinds of competitive dominance in exchange relations pursued by corporations with their associated strategy ceilings. Three of these forms of competitive dominance, the r-type task-system, c-type market-category and K-type market-channel forms, are based on vertically-dominant forms of governance, while P-type relational dominance is based on horizontally-dominant forms of governance. These different forms of competitive dominance are described in the blog on the governance of corporations and in the blog describing the left-hand side of the Double Diamond. Their corresponding forms of supracontract are based on the assumptions that remain implicit above the ceiling for each one, their progression being cumulative in the same way as are strategy ceilings, i.e., each kind of holobiont has to be able to manage its supporting contractual relations with symbionts and/or holobionts positioned back down the value stairs. From the perspective of a client system defined by those working for a corporation, these assumptions implicit above the strategy ceiling define the approach of the corporation’s sponsoring system.

The four different forms of competitive dominance are shown in Figure 3 by the coloring of the layers representing the different internalist relations of circular causality (shown in Figure 4 of the blog describing agency in living systems). The immune system of each of these forms of competitive dominance reflects a particular structure of identifications with behaviors above and below the strategy ceiling based on the form of circular causality in its behaviors. This structure of identification forms a structure of affiliation. The top brown apices in Figure 3 are added to the four layers to represent the supply-side structure of affiliation made available by that type of competitive dominance.[9]

The supracontract, then, is based on the assumptions that can remain implicit above the strategy ceiling, i.e., assumptions made by the corporation’s sponsoring system that are none of the business of those working for the corporation but that can be used as a basis for justifying the current governmentality. For the purchaser, however, the lower the strategy ceiling is, the more remains to be organized, orchestrated and synchronized by itself within its context-of-use. This context-of-use is represented by the faint blue layers in Figure 3 with their apex representing the purchaser’s relation to its value deficit.[10]

Figure 3: The governmentalities changing with the changes in causal texture.

The result from the perspective of the state are four different kinds of justification of supracontract, each one based on social agreement over what can remain implicit. Given that the value stairs describe the progressive development of exchange relations, these supracontracts too are cumulative in that each coexists with and/or has embedded within it the prior forms of supracontract (Karatani 2014[2010]). The transitions between them arise because of internal contradictions in each one’s justification that gives rise to its critique (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005). Each progression in governmentality thus reflects an adaptation in the state’s relation to its economy that responds to critiques of the previous governmentality. What follows is a gloss of each governing mentality, the form of supracontract it justifies, and its critique. These critiques bring us to consideration of the fourth governmentality, anticipated by Karatani in terms of the concept of commonwealth and the history of isonomia, i.e., equal treatment under the law (Karatani 2017[2012]):

- With r-type task-system dominance comes an extraction Justifications of ‘how’, ‘for whom’ and ‘why’ remain implicit. This governmentality assumes resource monopolies over the land and its resources, whether derived from Empire or established through feudal forms of social organization, monopolies that are justified by the monarchic or autarchic forms of power exercised. This was the dominant form of Western economies up to the end of the 19th century “essentially revolving around the actual influence of Protestantism on the development of capitalism and, more generally, of religious beliefs on economic practices, and drawing above all on Weber’s approach the idea that people need powerful moral reasons for rallying to capitalism.” (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005: p9). Disciplinary in its approach, we see it currently in economies dominated by the export of natural resources, its residual forms in the UK apparent in the governance of the Sovereign’s Estates.

The superstructures (Harland 1987) of patriarchy and inherited ownership that were the consequence of this extraction governmentality became subject to a Freudo-Marxist revolutionary critique because of the inequities accruing to the ruling family elites formed under its auspices. If this critique could not be ignored by the elites, it required them to open up access to wealth by the bourgeois entrepreneur in the form of industrial capitalism. Leading to the emergence of a middle class, this opening up brought with it an attendant benefit to the state in the creation of new forms of industrial wealth.

- With c-type market-category dominance comes a production Justifications of ‘for whom’ and ‘why’ remain implicit. This governmentality became dominant from the late 19th century to the years between the two world wars. It was characterized by technology monopolies exercised through the social organization of industrial capitalism and justified by hierarchical forms of power as ‘good for society’ (Lamb and Primera 2019). The internalization by customers of these hierarchical forms led to a biopolitics (Foucault 2008[2004]) legitimizing, for example, the role of the UK’s Civil Service Departments in administering different aspects of customers’ lives on the basis of its assumptions about ‘the good’, including England’s water industry. The justification here “owed less to economic liberalism, the market, or scientific economics, whose diffusion remained fairly limited, than to a belief in progress, the future, science, technology, and the benefits of industry”. (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005: p17)

The social critique of this production governmentality arose from “the egoism of private interests in bourgeois society and the growing poverty of the popular classes in a society of unprecedented wealth” (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005: p38). Unlike in World War I, in which it was still assumed that citizens would be prepared to die for the good of the country, fighting World War II needed a different contract with the citizen, if only so that women and minorities would be persuaded to join the war effort. Following World War II, this led to the state recognizing that providing some degree of public education, welfare and full employment had become necessary, leading in Western economies to various forms of social welfare supracontract with its citizens.

- With the closed form of the K-type market-channel dominance came a corporate While only the ‘why’ remained implicit, the ‘who-for-whom’ took a closed form defined by the market economics of the provider. Apparent from the pre-World War II years to the 1960s and dominated by the approach to consumerism in the USA, this was characterized by the fetishization of exchange value, its market economy dominated by corporate capitalism (Galbraith 1967). “Centered on the development of the large, centralized and bureaucratized industrial form, mesmerized by its gigantic size, its heroic figure was the manager. … [who was] preoccupied by the desire endlessly to expand the size of the firm he was responsible for, in order to develop mass production, based on economies of scale, product standardization, the rational organization of work, and new techniques for expanding markets (marketing) … these developments were marked by an attenuation of class struggle, a separation between ownership of capital and control of the firm, and signs of the appearance of a new capitalism, propelled by a spirit of social justice” (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005: pp17-18). Here the exercise of the supracontract between state and citizen led the state to form Quasi-Autonomous Non-Governmental Organizations (QANGOs) that could act on its behalf while remaining subject to its regulation. These were corporations that could serve the purposes of social welfare on behalf of the state, for example, the UK’s National Health Service or the privatized-but-regulated water industry.

The artistic critique of this market-channel dominance was based on the different affective experiences of citizens. Its roots were “on the one hand the disenchantment and inauthenticity, and on the other the oppression, which characterizes the bourgeois world associated with the rise of capitalism … [in] the loss of meaning and, in particular, the loss of the sense of what is beautiful and valuable, which derives from standardization and generalized commodification” (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005: p38). While justification of this corporate governmentality had come from a neoliberal approach to social welfare, offering choices organized by an affective politics, this form of closed K-type market-channel dominance was proving increasingly insufficient (Watson 1999).

- (continued) The open form of the K-type market-channel dominance sought to respond to this critique by making the ‘for whom’ assumptions open, derived explicitly from customers as a basis for defining market segments. While the ‘why’ assumptions continued to remain implicit, the neoliberal approach became dominated by opinion polling and focus groups pursuing the increasingly personal “by promoting the creation of products that [were] attuned to demand, personalized, and which [satisfied] ‘genuine needs’, as well as more personal, more human forms of organization” (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005: p99). These networked forms of organization sought to achieve this personalization by defining corporations more in terms of providing support to the citizen (Zuboff and Maxmin 2002) in an economy increasingly organized around affective politics (Davenport and Beck 2001). In furtherance of this justification and in support of a continuing corporate governmentality, the preemptive effects of narrativities and ‘wedge’ issues, disseminated by social media and designed to prime anxieties, made an affective politics possible even as it intensified affective networks that accentuated social differences (Massumi 2015).

The artistic critique of this ‘support economy’ was that it had become a form of ‘surveillance capitalism’ (Zuboff 2019) seeking to reinforce particular forms of affective sensibility that were only serving corporate interests.[11] The critique was that the corporate governmentality was justifying a supracontract that did not offer transparency of its operations and was not really based on a through-life duty of care to the well-being of its customers. Failures to meet this critique created fertile ground for populisms (Brubaker 2017, 2019) challenging the corporate governmentality’s assumptions about a corporate ‘why’ as it was being applied at the level of individual customers. To the extent that the open form of K-type market-channel dominance focused on the needs of particular individuals, the artistic critique was furthermore that it did so only in relation to the affluent minorities able to pay for it. This was not the experience of the majority of customers who remained subject at best to the closed form of K-type market-channel dominance (Porter and Kramer 2011).

This artistic critique persists in the present day, therefore, challenging the corporate governmentality to make a further adaptation justified by a further closing of the gap between corporate affiliation and the relation to customers’ through-life well-being. Such an adaptation requires a further degree of equalization in the balancing of interests between corporation and customer based on the ‘why’ becoming explicit. A closer look at the different forms of regulation associated with all four forms of supracontract provides insight into this fourth form of governmentality.

Regulatory approaches reflecting the different governmentalities.

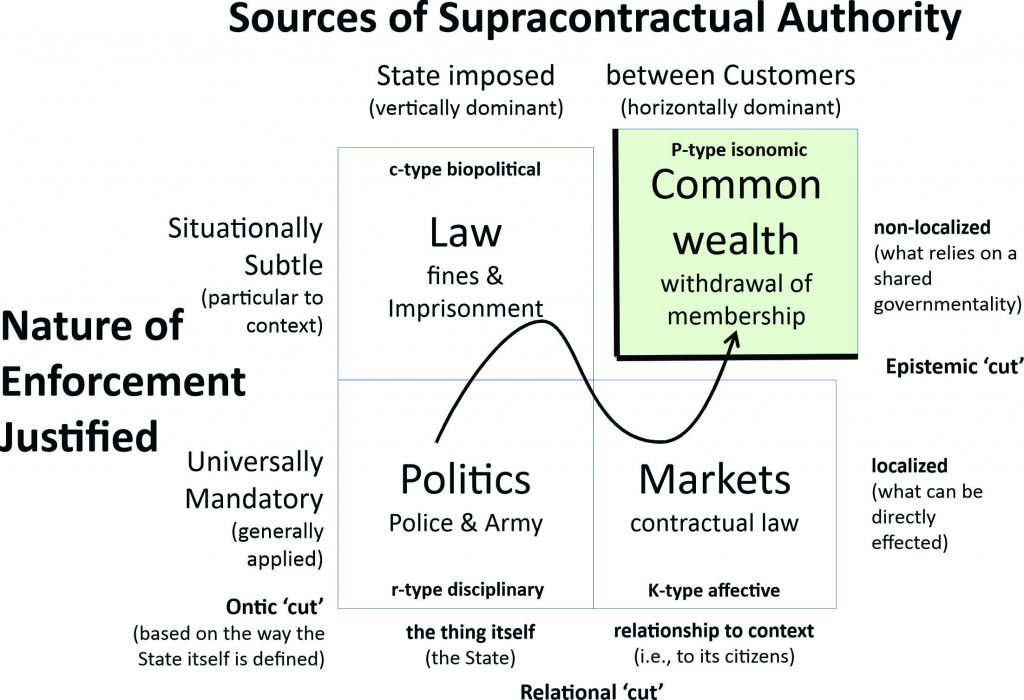

We can distinguish regulatory approaches by considering how they impact on the performance of an ecosystem. This involves understanding an ecosystem itself as being like a living system with its three ‘cuts’.[12] While the governing mentality reflects an architectural consistency of the ecosystem (the ‘upper hand’ in the previous blog), the externalist consistency is represented by the relations between the corporations within the strata of the ecosystem (the ‘lower hand’) and the internalist consistency is represented by the different forms of regulation of justifiable relations to customers within the ecosystem (the ‘globe’). Figure 4 summarises the externalist consistency, the architectural relations between the quadrants shown by the ‘zig-zag’. It is a version of the externalist consistency in the blog on the governance of corporations, but adapted to the governance of an ecosystem using Vibert’s work on democratic governance (Vibert 2014):

Figure 4: the challenge of governing the relational, adapted from (Vibert 2014)

- ‘Politics’ regulates through an r-type disciplinary approach justified by the economic interests of the ecosystem’s ruling elites, a justification based on the interests of the ecosystem vested in its resource monopolies;

- ‘Law’ regulates by extending the ‘political’ to a c-type biopolitical approach, justified by the corporations of the ecosystem having internalized an economic disciplinarity to which they are all subject, reinforced by the threat of fines and imprisonment while enabling the ecosystem’s industries to prosper; and

- ‘Markets’ regulate the K-type affective relations between corporations through the way those relations can take the form of economic transactional relationships between them subject to discrete contractual law (MacNeil 1980). It is the information asymmetries that emerge in the relations between either side of these discrete transactional relations that enable corporations to engage in oligopolistic or monopolistic behaviors with respect to their customers through which they can prosper within the ecosystem.

The transition to a commonwealth supracontract depends on contractual relations between customers that are also ‘situationally subtle’, i.e., that take context-of-use fully into account, possible only when relations between corporation and customer become subject to relational contract law (MacNeil 1980). This happens when the supracontractual norms are no longer based on discrete transactions but apply to a through-life exchange relationship based on the use-value of the relationship to the customer. Key here is the fact that establishing the economic value of such through-life relations depends on the digitalization of the relationship, the key characteristic of the Q-sectors[13]:

- A ‘commonwealth‘ regulates its P-type isonomic relations through the threat of withdrawing membership of that commonwealth, the penalties of that withdrawal arising from the loss of its through-life benefits. The justification of these isonomic relations, in which the members of the commonwealth are to be treated equally as peers, is in order for the long term benefits of its membership to emerge for all its members (Karatani 2017[2012]).

This commonwealth governmentality applies to the P-type relation between the corporations in an ecosystem and the ecosystem’s ultimate customers, as applies, for example, to the relations between city governance and the city’s residents (Pierre 2011). Here a pro-growth urban governmentality accelerates the growth of the city’s economy by focusing on growth in such a way that all its residents benefit from that growth (Pierre 2019). The governmentality necessary to the isonomic relations of a commonwealth, then, is one in which the P-type role of corporations within an ecosystem relate to their customers as its equals under the law, something that is very apparently not the case under K-type market-channel dominance (Harcourt 2011).[14]

Distinguishing the fourth governmentality

‘Commonwealth’ distinguishes the supracontractual norms regulating the Q-sector roles of corporations, regulating the P-type relations to customers within an ecosystem. With this supracontract, it is in the interests of a corporation to do as much as possible for its customers on a through-life basis without jeopardizing its sustainability (as opposed to doing as little as possible). Returning to Figure 3:

- With P-type relational dominance comes a commonwealth Relational dominance means that all four questions of the ‘what’, the ‘how’, the ‘for whom’ and the ‘why’ are explicit in the dynamics of the relationship. The conditions for relational strategies are apparent in the emergence of the Q-sectors of the economy enabled by the thick markets created by the vanishing hand of capitalism (Langlois 2007: p7, footnote 14; McLaren 2003). The role of the curator (Guillet de Monthoux 2022) provides a way of understanding what a commonwealth governmentality expects of the P-type role of a corporation: in the case of the water utilities, that they curate water services for their customers and be able to be held accountable to their customers for the way they do it over time.

In summary, then, The Q-sector supracontract justified by this fourth governmentality means that its focus still has to be on the way those P-type relations are themselves conducted. Given the asymmetric advantage that accrues in this context-of-use to the provider over its customers, however, the supracontract has to require transparency of information from the provider on its operating models accompanied by a commitment to a through-life duty of care to the well-being of its customers.

Notes

[1] The original definition of an economy was in terms of three sectors: 1 – extraction, 2 – production, 3 – service. The service sector has become so large in relation to the other two. In 2023 it was 81% of total UK economic output, 85% of employment and 56% of exports. As a consequence, it has been further broken down into 3 – distribution, 4 – alignment and 5 – cohesion, the value propositions in sectors 4 and 5 being knowledge-based.

[2] The justification of investments by their direct returns, i.e., ROI, has to be different for the Q-sectors, requiring Real Option analysis. This is because investment in platform infrastructures have to be justified on the basis of their enabling indirect returns across a wide variety of uses within each customer’s context-of-use. See (Boxer 2009).

[3] Picking up on Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in 1863, while the governing mentality addresses the approach to ‘government of the people’, the critiques of governmentalities below critique what is meant by ‘government by the people’ and the assertion that the ultimate selective pressures come from citizens addresses ‘government for the people’.

[4] ‘Relational contract’ is being used here in the sense of (Baker, Gibbons, and Murphy 2002) – “informal agreements sustained by the value of future relationships”. The more formal understanding of relational contracting, as the range of obligations that form the context for discrete transactions, was established by MacNeil (MacNeil 1978). Governmentality is thus understood as the means of justifying a particular form of supracontractual norm (MacNeil 1980: p70).

[5] The origins of this way of thinking about these norms comes from ‘The Shield of Achilles’ (Bobbitt 2002). The book traces the changes in their nature from the 15th Century to the end of the 20th. The book argues that these changes are driven by changes in the technologies of warfare, as a consequence of which the state has to change the basis on which it can expect its citizens to consent to the state’s powers over their lives and deaths. The particular ‘progression’ through feudal, industrial, market-based and commonwealth forms of governmentality are adapted from ‘The Structure of World History’ (Karatani 2014[2010]), the primary focus of which is on different modes of exchange within an economy rather than on the means of production.

[6] The Water Services Regulation Authority (https://www.ofwat.gov.uk/) for whom I did some work in 1997-98 with Professor Robin Wensley of Warwick Business School.

[7] Evaluating the potential returns on capital under such a regulatory approach is a great deal more complex, given that it has to be based on Real Option analysis in order to evaluate the impact of investment on a wide variety of possible situations See (Boxer 2009).

[8] Why would the UK government not now be insisting on a Q-sector supracontract for the water industry? The same issue came up with the privatization of the UK’s telecommunications industry, where unbundling of the ‘local loop’ became necessary to prevent an incumbent restricting competition (Ofcom 2005). It would appear to be because the UK government chose not to take through-life consequences into account in the way it made its decisions for the water industry and therefore had not set up such regulatory mechanisms. This lack of regulatory mechanisms also became apparent in the case of orthotics provision within the UK’s national health Services (Flynn and Boxer 2004; Hutton and Hurry 2009). This blog suggests that to set up such regulatory mechanism would involve the Government no longer being able to reserve to itself the ‘why’ justifications associated with its corporate governmentality.

[9] ‘Supply-side’ because each type of competitive dominance involves a particular way of organizing the means of production.

[10] The ‘value deficit’ is that which remains to be desired by the purchaser after its demands have been responded to by its providers. The underlying dialectic between purchaser and provider is based on their complementarity and is described in the blog on ‘20th versus 21st century capitalism’. My original understanding of this complementarity comes from Illich’s treatment of the relation to the vernacular (Illich 1982: p68) and to shadow work (Illich 1981).

[11] Doing this involved an affective politics reinforcing identifications of the third kind, the form of identification that is to a particular affective relation to a situation (Freud 1955). My originally optimistic view of social media as being emancipatory of such identifications (Boxer 2011) failed to anticipate how the use of social media would not escape the corporate governmentality. The potential for social media to fuel emancipation of authorship remains, however, the artistic critique being apparent in their disruptive effects (Boxer 2013).

[12] As we shall see, it is only with the fourth governmentality that the focus of the governmentality moves fully to being on the customers of the ecosystem per se. The challenges of this relation between corporations within an ecosystems are present in the focus on developing industry clusters. See (Porter 1990, 1998; Donahue, Parilla, and McDearman 2018; Leydesdorff and Zawdie 2010; Zhou and Etzkowitz 2021).

[13] See (Hulten and Nakamura 2018, 2019; Miron et al. 2019; Coyle 2017; Coyle and Mitra-Kahn 2017) for some of the challenges this presents to existing governmentalities.

[14] Note that in the case of social media corporations, the information asymmetry enables them to behave as if open K-type while in fact being closed K-type.

References

Baburoglu, Oguz N. 1988. ‘The Vortical Environment: The Fifth in the Emery-Trist Levels of Organizational Environments’, Human Relations, 41: 181-210.

Baker, George, Robert Gibbons, and Kevin J. Murphy. 2002. ‘Relational Contracts and the Theory of the Firm’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117: 39-84.

Bobbitt, P. 2002. The Shield of Achilles: War, Peace and the Course of History (Allen Lane: London).

Boltanski, L., and E. Chiapello. 2005. The New Spirit of Capitalism (Verso: London).

Boltanski, L., and L. Thevenot. 2006[1991]. On Justification: Economies of Worth (Princeton University Press).

Boxer, P.J. 2009. “What Price Agility? Managing Through-Life Purchaser-Provider Relationships on the Basis of the Ability to Price Agility.” In. Pittsburgh: CMU/SEI-2009-SR-031 unlimited distribution.

———. 2011. ‘The Twitter Revolution: how the internet has changed us.’ in H. Brunning (ed.), Psychoanalytic Reflections on a Changing World (Karnac: London).

———. 2013. ‘Managing the Risks of Social Disruption: What Can We Learn from the Impact of Social Networking Software?’, Socioanalysis, 15: 32-44.

Brubaker, Rogers. 2017. ‘Why Populism?’, Theory and Society, 46: 357-85.

———. 2019. ‘Populism and Nationalism’, Nations and Nationalism, 26: 44-66.

Coyle, Diane. 2017. ‘Rethinking GDP’, Finance & Development, 54.

Coyle, Diane, and Benjamin Mitra-Kahn. 2017. “Making the Future Count.” In Indigo Prize Entry. http://global-perspectives.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/making-the-future-count.pdf.

Davenport, Thomas, and John Beck. 2001. The Attention Economy; Understanding the New Currency of Business (Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, MA).

Donahue, Ryan, Joseph Parilla, and Brad McDearman. 2018. “Rethinking Cluster Initiatives.” In Metropolitan Policy Program. Brookings Institute.

Flynn, T., and P.J. Boxer. 2004. “Orthotic Pathfinder Report.” In.: Business Solutions Ltd.

Foucault, M. 2008[2004]. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the College de France, 1978-1979 (Palgrave Macmillan: New York).

Freud, S. 1955. ‘Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921).’ in, translated and edited by J. Strachey, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud Volume XVIII (1920-1922) (The Hogarth Press: London).

Galbraith, John K. 1967. The New Industrial State (Hamish Hamilton: London).

Guillet de Monthoux, Pierre. 2022. Curating Capitalism: How Art Impacts Business, Management, and Economy (Sternberg Press: Stockholm School of Economics).

Harcourt, B.E. 2011. The Illusion of Free Markets: Punishment and the Myth of Natural Order (Harvard University Press: Cambridge).

Harland, Richard. 1987. Superstructuralism: The Philosophy of Structuralism and Post-Structuralism (Methuen: London & New York).

Hulten, Charles R., and Leonard I. Nakamura. 2018. “Accounting for Growth in the Age of the Internet: The Importance of Output-Saving Technical Change.” In. https://doi.org/10.21799/frbp.wp.2017.24: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Research.

———. 2019. “EXPANDED GDP FOR WELFARE MEASUREMENT IN THE 21ST CENTURY.” In. http://www.nber.org/papers/w26578: NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH.

Hutton, J., and M. Hurry. 2009. “Orthotic Service in the NHS: Improving Service Provision.” In.: York Health Economics Consortium.

Illich, Ivan. 1981. Shadow Work (Marion Boyars: New York).

———. 1982. Gender (Marion Boyars: New York).

Karatani, Kojin. 2014[2010]. The Structure of World History: from modes of production to modes of exchange (Duke University Press: Durham and London).

———. 2017[2012]. Isonomia and the Origins of Philosophy (Duke University Press: Durham and London).

Lamb, Melanya, and German E. Primera. 2019. ‘Sovereignty between the Katechon and the Eschaton: Rethinking the Leviathan’, Telos, 187: 107-27.

Langlois, R.N. 2007. The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism: Schumpeter, Chandler and the New Economy (Routledge: London).

Langlois, Richard N. 2003. ‘The Vanishing Hand: the changing dynamics of industrial capitalism’, Industrial and Corporate Change, 12: 351-85.

Laville, Sandra. 2023. ‘Treated and untreated sewage greatest threat to river biodiversity, says study’, The Guardian.

Laville, Sandra, and Anna Leach. 2022. ‘Water firms’ debts since privatisation hit £54bn as Ofwat refuses to impose limits’, The Guardian, 1 December 2022.

Leach, Anna, Carmen Aguilar Garcia, and Sandra Laville. 2022. ‘Revealed: more than 70% of English water industry is in foreign ownership ‘, The Guardian, 30 November 2022.

Leach, Anna, Ellen Wishart, Sandra Laville, and Carmen Aguilar Garcia. 2023. ‘Down the drain: how billions of pounds are sucked out of England’s water system’, The Guardian, 28 June 2023.

Leydesdorff, Loet, and Girma Zawdie. 2010. ‘The Triple Helix Perspective of Innovation Systems’, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 22: 789-804.

MacNeil, Ian R. 1978. ‘Contracts: adjustment of long-term economic relations under classical, neoclassical and relational contract law’, Northwestern University Law Review, 72: 854-901.

———. 1980. The New Social Contract: an Inquiry into Modern Contractual Relations (Yale University Press).

Massumi, Brian. 2015. The Power at the End of the Economy (Duke University Press: Durham and London).

McLaren, J. 2003. ‘Trade and market Thickness: Effects on Organizations’, Journal of the European Economic Association, 1: 328-36.

Miron, Dumitru, Dragos Seuleanu, Cezar Radu Cojocariu, and Laura Benchea. 2019. ‘The European Model of Development faced with the Quaternary Sector Emergence Test’, Amfiteatru Economic, 21: 743-62.

Ofcom. 2005. “Local loop unbundling: setting the fully unbundled rental charge ceiling and minor amendment to SMP conditions FA6 and FB6.” In. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/36691/llu_statement.pdf: Office of Communications.

Pierre, Jon. 2011. The Politics of Urban Governance (Palgrave Macmillan: New York).

———. 2019. ‘Institutions, politicians or ideas? To whom or what are public servants expected to be loyal?’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 21: 487-93.

Porter, M. E. 1990. The Competitive Advantage of Nations (Free Press: New York).

———. 1998. ‘Clusters and the New Economics of Competition’, Harvard Business Review, 76: 77-90.

Porter, M. E., and M.R. Kramer. 2011. ‘Creating Shared Value: How to reinvent capitalism – and unleash a wave of innovation and growth’, Harvard Business Review: 2-17.

Strukhoff, Roger. 2016. “”Q Sectors”: Global Digital Transformation Leads to Economic Growth.” In Altoros. https://www.altoros.com/blog/software-dev-the-worlds-q-sectors/.

Vibert, Frank. 2014. The New Regulatory Space: Reframing Democratic Governance (Edward Elgar: Elgaronline).

Watson, Sean. 1999. ‘Policing the Affective Society: Beyond Governmentality in the Theory of Social Control’, 8: 227-51.

Zhou, Chunyan, and Henry Etzkowitz. 2021. ‘Triple Helix Twins: A Framework for Achieving Innovation and UN Sustainable Development Goals’, Sustainability, 13.

Zuboff, S. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (PublicAffairs: New York).

Zuboff, S., and J. Maxmin. 2002. The Support Economy: Why Corporations are Failing Individuals and the Next Episode of Capitalism (Viking: New York).