Using the biological metaphors from the 2nd blog, we have approached a corporation as being like a holobiont understood as being operationally and managerially independent. This enables us to include a corporation’s constituent business units, subcontractors and outsourced services as symbionts while including the possibility that those symbionts may also be playing the same role for other holobionts. This enables the definition of an ecosystem to be restricted to the interactions between holobionts and the definition of a superorganism to be restricted to the social organization of holobionts. This enables the concept of governance to be applied to a holobiont and the concept of governing mentalities, i.e., governmentalities, to be applied to the social organization of supersystems. Thus, for example, while the industry association for the machine tool industry is a superorganism, the corporations providing health care to individuals form an ecosystem. This distinction will become important in the last blog in this series when we consider the regulation of an ecosystem under different forms of governmentality.[1]

Bearing in mind the three consistencies

Changes in the environment of a corporation create new selective pressures whether or not consideration of the doubled double task, introduced in the 1st blog, needs to be internalized as a general property of a corporation because of its having to compete in turbulent environments. These selective pressures require that a corporation’s governance must be holding in mind all three of its consistences as a living system, introduced in the 4th blog. Figure 1 provides a visual metaphor for the interdependence of these three consistencies:

Figure 1: A metaphor for the relations between the three consistencies of a corporation as a living system

- the internalist consistency, represented by the ‘globe’, of how vertical and horizontal accountabilities are held in relation to each other in delivering the corporation’s particular type(s) of value proposition,

- the externalist consistency, represented by the supporting ‘lower hand’, of how these value propositions are themselves part of the stratified ecosystems of which they are a part, and

- the architectural consistency, represented by the steadying ‘upper hand’, of how the identifications of all those working for the corporation are invested in the corporation’s value-creating behaviors, identifications that collectively form a cultural immune system. The effects of this immune system are evidenced by the forms of agility that the corporation is invested in across eight symptomatic lines of capability development.[2]

The challenge of adaptation

What makes the accelerating tempo of demand-side change in turbulent environments so challenging, continuing with the visual metaphor in Figure 1, is that the externalist ‘bottom hand’ will be moving as an ecosystem adapts to demand-side selective pressures. The ‘bottom hand’ will also be moving as the corporations within an ecosystem adapt to supply-side pressures emerging from the internal dynamics of that ecosystem. These dynamics will be driven by its corporations choosing to acquire new products and services and/or to develop new ways of integrating operational capabilities. Regardless of the sources of the ‘bottom hand’ movement, however, for the architectural ‘upper hand’ not to stay aligned to a moving externalist ‘bottom hand’ is for the internalist ‘globe’ to risk falling/failing as in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The corporation falls if the three consistencies fail to stay aligned.

If we leave aside whether or not the corporation’s immune system is staying aligned, two questions arise concerning what alignment looks like:

- How are the corporation’s value propositions positioned on a ‘value stairs’ describing the ‘bottom hand’ stratification of the ecosystem within the context of other competitors and customers; and

- In the ‘double diamond’, is the balance between the horizontal and vertical axes of governance within the ‘globe’ congruent with the way value propositions are positioned on the ‘value stairs’.

While the ‘double diamond’ (Boxer and Veryard 2006) addresses the congruence between the internalist (left-hand side diamond) and externalist (right-hand side diamond) consistencies, the level of the strategy ceiling on the ‘value stairs’ below reflects the particular way in which the cultural immune system is invested in whatever form of congruence has been adopted (Boxer and Wensley 1996; Boxer 2017).

Positioning of value propositions on the ‘value stairs’

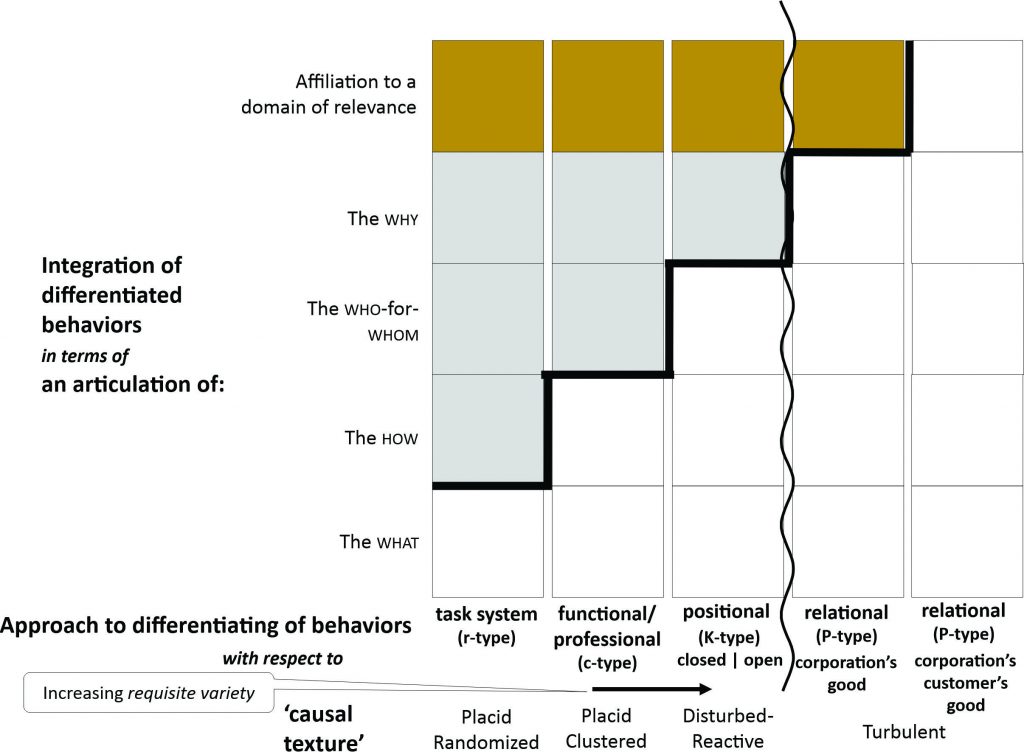

The architectural stratified consistency introduced in the previous blog relates the underlying technologies used by an ecosystem to the demands generating selective pressures on it, the stratification shaped by the corporations’ value propositions within the ecosystem. This stratification can be thought of as defining a ‘value stairs’ (see Figure 3). A corporation’s place along the x-axis on these ‘stairs’ reflects the increasing requisite variety of behaviors (Ashby 1956) necessary to meeting the competitive demands within a progressive complexification of the environment, described as its causal texture (Emery and Trist 1965).

To be sustainable, a corporation’s place on these ‘stairs’ along the x-axis has to be matched by a corresponding ability to integrate its differentiated behaviors along the y-axis (Lawrence and Lorsch 1967). Above the strategy ceiling at each step on the ‘stairs’ are the integrating assumptions that can remain implicit. Below the ceiling are the integrating assumptions that need to be explicit because needing to be dynamically responsive to that step’s competitive dynamics.

A corporation’s place on these ‘stairs’ will include the supporting propositions back down the ‘stairs’, whether because they are from symbionts internal or subcontracted to the corporation, or acquired from other corporations in the ecosystem. The ‘stairs’ thus relate this architectural consistency of the ecosystem’s stratification to the externalist consistency of the different types of value proposition being integrated by corporations, each with its characteristic strategy ceiling. It is the cultural immune system that restricts the ability of a corporation to move up or down the ‘stairs’, despite competitive pressures[3], because of the particular ways in which its individuals conserve their identifications with the corporation’s current ways of creating value.

Figure 3: Positioning on the value stairs.

Figure 3: Positioning on the value stairs.

Regardless of where an individual corporation chooses to place itself on the ‘stairs’ within a particular ecosystem, however, it does so within the context of the other corporations and corporate symbionts spanning the other places up and down the ‘stairs’. Each of these corporations will have its particular configuration of purchaser-provider relations that will be subject to change as the ecosystem responds to selective pressures.[4] Corporations will also be occupying places within other ecosystems, for example in the provision of healthcare in multiple regions, while also participating in supersystems such as industry associations. The last blog in this series considers different ways in which these supersystems may be organized socially and the implications of these different forms of governmentality for the way the behaviors of corporations are regulated.

The ‘double diamond’ balance between the horizontal and vertical axes of governance

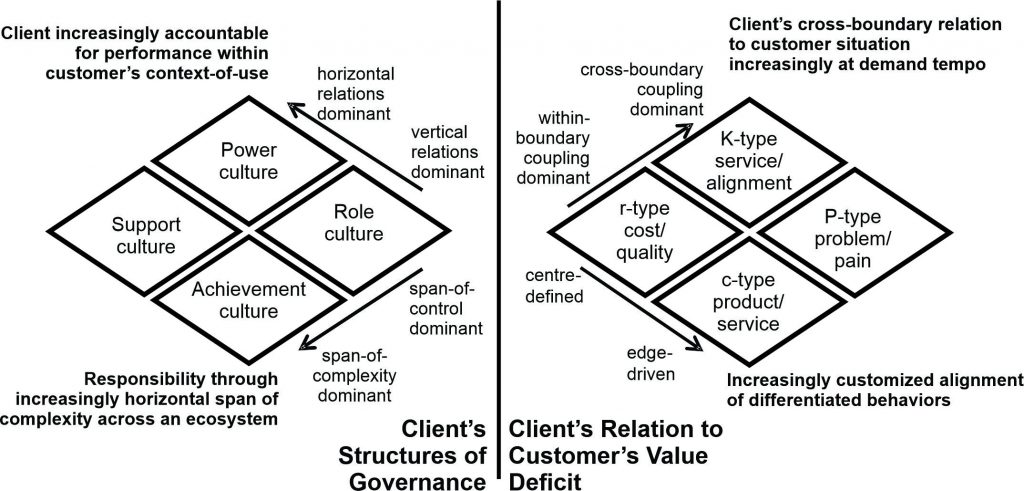

The right-hand side (RHS) of the ‘double diamond’ in Figure 4 describes the way a corporation’s value proposition relates to its customers within the ecosystem in which the corporation is competing. Here the four types of value proposition from the previous blog are described in terms of two dimensions:

- The way its behaviors are defined, moving from being behaviors defined by the center of the corporation to its behaviors being defined at its edges by each customer relation.

- The way those behaviors are coupled to the operational dynamics of the customer’s context-of-use, moving from being wholly uncoupled from the customer’s demand tempo to being tightly coupled.

Figure 4: The congruence of a corporation’s governance with its value propositions

Figure 4: The congruence of a corporation’s governance with its value propositions

The left-hand side (LHS) of the ‘double diamond’ describes the governance of the corporation, also in terms of two dimensions:

- The way the responsibilities of roles are defined, moving from the role’s span-of-control being dominant to its span-of-complexity being dominant[5].

- The way accountability for performance is defined, moving from vertical accountability to the top of a hierarchy being the dominant criterion of success to horizontal accountability to the customer within its context-of-use being the dominant criterion.

The names of the quadrants in the LHS diamond distinguish what it feels like to be working in each quadrant: the alienation of a role culture, the potential for burnout in an achievement culture, the necessary alignment to task leadership in the power culture and the enabling nature of a support culture (Harrison 1987). Each one of these quadrants reflects a different way of balancing the vertical and horizontal axes of accountability in a corporation. The two diamonds are mirror images of each other, albeit each with its own dynamics. Examining the congruence of positionings on the LHS and the RHS provides a way of examining the alignment between the (LHS) ‘globe’ governance and the (RHS) positioning of the corporation’s value propositions within the ecosystems in which it is competing.

Implications

For the architectural ‘upper hand’ not to be staying aligned with a moving ‘bottom hand’, the corporation’s cultural immune system has to be insisting on remaining attached to ways of ‘using’ the behaviors of its current value propositions, represented by the ‘globe’, even while the ‘bottom hand’ ecosystem is moving away from valuing the places presently occupied by those propositions.[6] This falling/failing doesn’t necessarily happen immediately, quasi-monopolies making it possible to ignore changes in the demand environment for a long time if current governmentalities do nothing to encourage it. For example, using a market justification for externalizing costs on other corporations and customers, i.e., on externalities from the perspective of the corporation, enables a corporation to delay the need for adaptation.[7]

While the implicit sanctioning of such maladaptation by an existing governmentality may create opportunities for corporations, it will also lead to market failures. ‘Market failure’ here means that a market-defining aggregation of demand cannot be economically justified on the basis of capturing economies of scale and scope (Langlois 2003). This leads to the complexity issues not addressed by market offerings having to be picked up by customers within their contexts-of-use. As market offerings become less and less effective in meeting the demands of a customer’s context-of-use, the customer’s environment becomes increasingly vortical (Baburoglu 1988), overwhelmed by having to manage constraints imposed by suppliers in addition to dealing with the dynamics of their own situation.

The growth in the Q-sectors of the economy (Strukhoff 2016), i.e., the knowledge-based sectors four and five[8], represents a value-creating response both to this intensifying dynamic complexity and to these market failures. The associated growth in open K-type and P-type propositions is based on being able to capture economies of alignment, or of governance as Williamson puts it (Williamson 2005), through using digitalization to make possible the dynamic orchestration and synchronization of operational capabilities.[9] The last blog in this series considers what form of governmentality is enabling of the Q-sectors.

Notes

[1] The challenges of regulation were explored by Trist in terms of referent organizations defined by their relation to a particular domain (Trist 1983, 1977). A ‘referent organization’, previously described as ‘regulative’ (Trist 1981), was distinguished from an ‘operational organization’: while the latter engaged in exchange processes with their environments, the former organized how the latter behaved within a particular domain in the sense of a context-of-use. See ‘Leading organizations without boundaries’ (Boxer 2014) for more on the implications of this distinction between referent and operational organizations.

[2] These lines of development (LoDs) are ‘symptomatic’ because they represent the ways in which different forms of leadership in the corporation’s libidinal economy are invested in and realized. Their definition is adapted from the USA’s and UK’s understanding of what it takes to turn acquired technological capabilities, i.e., ‘tools’, into effective behaviors (Boxer 2009a). They are ‘Doctrine & Operational Concepts’, ‘Facilities, Infrastructure & Logistics’, ‘Leadership & Education’, ‘Materiel & Technology’, ‘Edge Organization’, ‘Mission Alignment & Interoperability’, ‘Situational Understanding’ and ‘Personnel & Culture’. Each LoD can be characterized by the degree of agility in the way it has been realized.

[3] Regardless of the constraints introduced by a corporation’s immune system, moving down the ‘stairs’ is easier than moving up them because moving down is less demanding of the behaviors needing to be integrated. The ultimate driver of these competitive pressures is the sustainability of the corporation’s ROI performance represented by where the corporation is above or below the equilibrium-ROI surface. This equilibrium surface is defined by the corporation’s performance in relation to its competitors based on the relation it takes up to each of the three architectural asymmetries. See https://asymmetricleadership.com/2006/04/06/must-we-fall-into-the-vortex/.

[4] ‘Effects ladders’ are a way of describing the nature of the overall demand-side selective pressures on the ecosystem. See ‘Understanding Value Propositions and Effects Ladders’ (Boxer 2002).

[5] Span-of-complexity is referred to by Jaques as ‘timespan of discretion’ (Jaques, Gibson, and Isaac 1978). Span-of-complexity emphasizes the horizontal boundary-spanning nature of a role as well as its through-time characteristics.

[6] Because identifications supported by a corporation’s behaviors collectively form an immune system, the systemic characteristics of which may be described as a ‘libidinal economy of discourses’ (LEoD), for the architectural ‘upper hand’ to be able to move, there has to be a circulation of discourses in this LEoD (Boxer 2021).

[7] The governmentality associated with market justification is one way of understanding how corporations have been enabled to ignore climate change. The last blog in this series argues that a state with an investment in this way of managing the economy, i.e., in a neo-liberal governmentality, will have vortical consequences for its citizens that a ‘commonwealth’ governmentality will not. A ‘commonwealth’ governmentality, however, will need to regulate the economy differently in order to strike a different balance between the interests of corporations and citizens.

[8] The original definition of an economy was in terms of three sectors: 1 – extraction, 2 – production, 3 – service. The service sector has become so large in relation to the other two that it has been further broken down into 3 – distribution, 4 – alignment and 5 – cohesion, the value propositions in sectors 4 and 5 being knowledge-based.

[9] The justification of investments by their direct returns, i.e., ROI, has to be different for the Q-sectors, requiring Real Option analysis. This is because investment in platform infrastructures have to be justified on the basis of their enabling indirect returns across a wide variety of uses. See (Boxer 2009b).

References

Ashby, W. Ross. 1956. An Introduction to Cybernetics (Chapman & Hall: London).

Baburoglu, Oguz N. 1988. ‘The Vortical Environment: The Fifth in the Emery-Trist Levels of Organizational Environments’, Human Relations, 41: 181-210.

Boxer, P.J. 2002. “Understanding Value Propositions and Effects Ladders.” In. www.brl.com: Boxer Research Ltd.

———. 2009a. “Building Organizational Agility into Large-Scale Software-Reliant Environments.” In IEEE 3rd International Systems Conference, 377-80. Vancouver, BC: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/4815830.

———. 2009b. “What Price Agility? Managing Through-Life Purchaser-Provider Relationships on the Basis of the Ability to Price Agility.” In. Pittsburgh: CMU/SEI-2009-SR-031 unlimited distribution.

———. 2014. ‘Leading Organisations Without Boundaries: ‘Quantum’ Organisation and the Work of Making Meaning’, Organizational and Social Dynamics, 14: 130-53.

———. 2017. ‘Working with defences against innovation: the forensic challenge’, Organizational and Social Dynamics, 17: 89-110.

———. 2021. “Working Beyond The Pale: when doesn’t it become an insurgency?” In ISPSO Annual Conference. Berlin.

Boxer, P.J., and Richard Veryard. 2006. ‘Taking Governance to the Edge’, Microsoft Architect Journal: http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/architecture/bb245658.aspx?ppud=4.

Boxer, P.J., and J.R.C. Wensley. 1996. “Performative Organisation: Learning to Design or Designing to Learn.” In. BRL Working paper: Warwick Business School.

Emery, F.E., and E.L. Trist. 1965. ‘The Causal Texture of Organizational Environments’, Human Relations, 18: 21-32.

Harrison, Roger. 1987. Organisation Culture and Quality of Service: a strategy for releasing love in the workplace (The Association for Management Education and Development: London).

Jaques, E., R.O. Gibson, and D.J. Isaac (ed.)^(eds.). 1978. Levels of Abstraction in Logic and Human Action (Heinemann: London).

Langlois, Richard N. 2003. ‘The Vanishing Hand: the changing dynamics of industrial capitalism’, Industrial and Corporate Change, 12: 351-85.

Lawrence, Paul R., and Jay W. Lorsch. 1967. ‘Differentiation and Integration in Complex Organizations’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 12: 1-47.

Strukhoff, Roger. 2016. “”Q Sectors”: Global Digital Transformation Leads to Economic Growth.” In Altoros. https://www.altoros.com/blog/software-dev-the-worlds-q-sectors/.

Trist, Eric. 1977. ‘A Concept of Organizational Ecology’, Australian Journal of Management, 2: 161-76.

———. 1981. ‘The Evolution of Socio-Technical Systems.’ in A.F Van de Ven and W.F. Joyce (eds.), Perspectives on Organizational Design and Behaviour (John Wiley: New York).

———. 1983. ‘Referent Organizations and the Development of Inter-Organizational Domains’, Human Relations, 36: 269-84.

Williamson, Oliver E. 2005. ‘The Economics of Governance’, American Economic Review, 95: 1-18.