by Philip Boxer

The leadership of learning from experience involves learning from direct experience of practice – what is sometimes called action learning. This approach depends on establishing a ‘transference to the work’ in the sense that the learning has to be allowed to emerge through engaging with the problematic nature of a situation in practice. It contrasts with consultancy, in which the learning needed is b(r)ought in, based on a transference to the consultant. How this choice is taken up, between consultancy or action learning, will reflect the way power is exercised by the sponsoring system[1] within the client organisation.

The leadership environment

Action learning demands a leadership environment that holds the balance between[2]:

- is prepared to acknowledge problems that need tackling (E);

- provides support to tackling them (S);

- recognizes career paths that make use of action learning (W);

- uses as process models successful examples of action learning that become taken up by the larger organization (N);

Correspondingly, to be effective, any action learning project has to be able to satisfy four ‘edge’ criteria while keeping them in balance[3]:

- It should add value (E): the outcome of the project should be to give the organisation a new ‘angle’ and new leadership in the way it creates value for its client.

- It should be practical (S): the project should be based on data, make effective use of existing capabilities, and the result of the project should produce ground-level consequences for the way these capabilities are used.

- It should ‘connect’ (W): the project should build on or take account of existing structures and ‘culture’ of vested interests, i.e. it must take notice of what is possible.

- It should matter (N): there should be an identified sponsor[1] for the project to whom the team can relate and report.

The facilitating role

Crucial to the success of such projects is the person in the facilitating role[4], whose task it is to enable the members of the project to engage in a a ‘plus-one’ process. This type of process is needed to work through each of the following potential sources of error[5] in how they approach their learning:

- Is the project team placing too much dependence on one account of what is going on? (is it buying in to one person’s version of the story, as though he or she knew and could give a total description of the problem situation?)

- Is the project team assuming that there will be one right way to interpret the presented problem? (is a particular frame of reference being accorded unquestioned authority?)

- Where does the project team ‘draw the line’ around the problem? Is the line being drawn in a way which includes or excludes themselves? (Who is part of whose problem in the problem-as-presented, and are the project team able to formulate the problem in a way which includes themselves?)

The relation to the larger organization

One reason why changes introduced by action learning projects do not get taken up by the larger organization is because they are not understood by the larger organization as sources of collaborative learning[2]:

- mobilizing commitment to change through joint diagnosis of business problems.

- developing a shared vision of how to organize and manage for effectiveness.

- fostering consensus for a new vision, competence to enact it, and cohesion to move it along.

- spreading revitalization to all parts of an organization without pushing from the top.

- institutionalizing learning through formalizing supporting policies, systems and structures.

- enabling strategies to be monitored and adjusted to problems encountered in the process of institutionalization.

The importance of networking across boundaries

Another reason is because such projects remain locked inside organizational silos, and are not used to reshape the organization by developing E-W dominance[6]:

- Using action learning projects as change agents to create a new ‘social architecture’, becoming the basis of networks, determining the intensity, substance, output, and quality of interactions; as well as the frequency and character of dialogue among members of the network.

- Defining with clarity and specificity the business outputs expected of the action learning project and the timeframe in which it is expected to deliver.

- Guaranteeing the visibility and free flow of information to all members of a network and promoting simultaneous communication (dialogue) among them.

- Developing new criteria and processes for performance evaluation and promotion that emphasize horizontal collaboration through networks, openly sharing these performance measurements with all members of the network and adjusting them in response to changing circumstances.

Notes

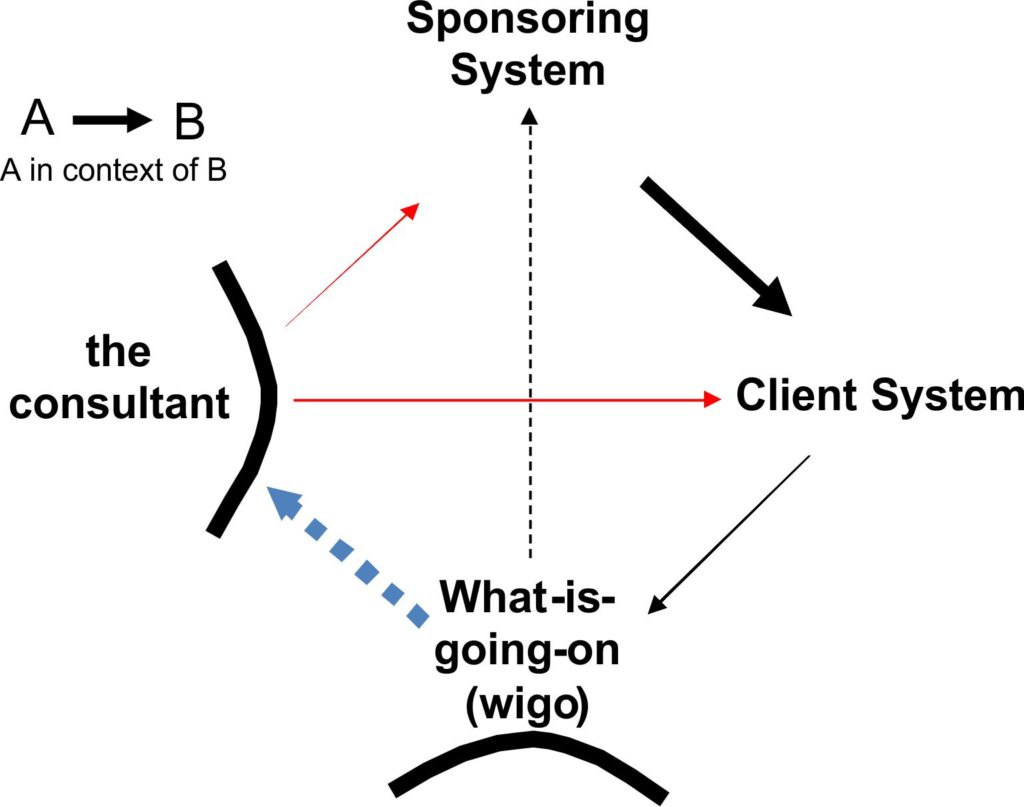

[1] The client system is where the ‘problem’ is, but the sponsoring system is where the power is. So the consultant has to work with the problem within the context defined by the sponsor:

The relation between these two axes parallels the relation between the two axes in the the plus-one process.

[2] The source of this list is ‘Why Change Programs Don’t Produce Change’, by by Michael Beer, Russell A. Eisenstat, and Bert Spector, Harvard Business Review, November–December 1990. Some of the challenges involved in doing this are described in the paper on The Future of Identity

[3] The N-S-E-W refer to the balance that needs to be sustained by the governance system in order to overcome a North-South bias. The use of this approach in one organisation is described in this paper on Marketing Project Groups.

[4] The challenges of this enabling role are described in this paper on meeting the challenge of the case.

[5] These lead to the three kinds of error in ‘Unintentional’ errors and unconscious valencies:

- Type I errors of correspondence arising from placing too much dependence on one account of what is going on,

- Type II errors of coherence/consistency arising from having assumed there will be one right way to interpret the presented problem, and

- Type III errors of intent arising from leaving the project team’s own interests (and therefore valencies) out of the way the problem is formulated.

[6] The source of this list is ‘How Networks Reshape Organizations – For Results’, by Ram Charan, Harvard Business Review, September-October 1991. Some of the challenges surrounding the formation of network interventions are described in this blog on stratification.