by Philip Boxer BSc MBA PhD

A recent examination of the Leadership Qualities Framework, developed by the UK’s National Skills Academy, shows just how difficult it is to counteract the bias of North-South dominant assumptions about governance and leadership[1], even as in this case where there is very clearly a wish to do so.[2] This bias becomes apparent in the assumptions made about the nature of strategy and its relation to hierarchy.

Policy, Strategy and Tactics

The framework gives a special role to strategic leadership with its own additional qualities: creating the vision and delivering the strategy. In the forward to this framework, Norman Lamb MP points out the following:

Good social care has the potential to transform people’s lives. It can help them realise independence, exercise meaningful choice and control over the care and support they receive, and live with dignity and opportunity. Good social care has the potential to transform people’s lives. It can help them realise independence, exercise meaningful choice and control over the care and support they receive, and live with dignity and opportunity. High quality leadership, embedded throughout the social care workforce, is fundamental to the delivery of high quality care. At the same time, we need to reach beyond the workforce and bring leadership skills and capabilities to service users, their carers and the communities in which they live and work.

For leadership to fulfill this promise, it must at least aspire to responding to people’s lives one-by-one. Put another way, in order to transform a person’s life, a particular combination of services need to be dynamically aligned to that person’s needs over time that remain particular to that person’s situation and context. This alignment of services has to be run East-West to reflect the fact that its design is inevitably entangled with the way they impact on that person’s experience.

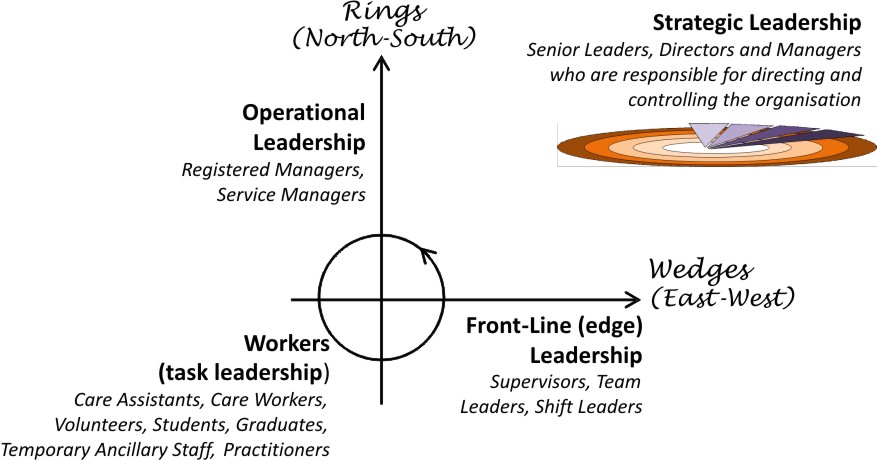

This means that leadership has to enable the organisation to hold a dilemma – a tension between securing economies of scale and scope from the way component services are provided, and securing economies of alignment from the way these component services are combined in relation to any one person’s needs. This tension can be represented by the concept of rings and wedges: rings (securing economies of scale and scope) can provide well-defined services that are effectively provided by North-South dominant forms of governance, while wedges (securing economies of alignment) align combinations of services in particular ways that can be effectively provided by East-West dominant forms of governance.

This means that leadership has to enable the organisation to hold a dilemma – a tension between securing economies of scale and scope from the way component services are provided, and securing economies of alignment from the way these component services are combined in relation to any one person’s needs. This tension can be represented by the concept of rings and wedges: rings (securing economies of scale and scope) can provide well-defined services that are effectively provided by North-South dominant forms of governance, while wedges (securing economies of alignment) align combinations of services in particular ways that can be effectively provided by East-West dominant forms of governance.

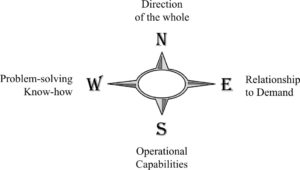

So what is wrong with thinking in terms of strategy-and-tactics? The industrial world names as ‘strategy’ what the military calls ‘operations’, while the industrial world names as ‘policy’ what the military calls ‘strategy’.[3] Relating the industrial names to the NSEW model<sup[4],

- tactics are about using know-how(W) to make the best possible use of capabilities(S),

- strategy is about developing the most effective know-how(W) for addressing a particular kind of demand(E), and

- policy is about determining what variety of demands(E) can be addressed within the context of the organisation as a whole(N).

The point about East-West alignment is therefore that strategy has to be determined at the level of the individual wedge and it is the policy frame that creates the conditions at the level of the organisation as a whole within which the ring-wedge dilemmas can be supported effectively. Strategy has to be held at the edge of the organisation within a unifying policy frame.

The vertical and the horizontal axes of governance

Which brings us to the relation of strategy and hierarchy. The Leadership Qualities Framework proposes that it be applied at four levels of leadership as follows:

- Front-line Worker – Care Assistants, Care Workers, Volunteers, Students, Graduates, Temporary Ancillary Staff and Practitioners

- Front-line Leadership – Supervisors, Team Leaders, Shift Leaders

- Operational Leadership – Registered Managers, Service Managers

- Strategic Leadership – Senior leaders, Directors and Managers who are responsible for directing and controlling the organisation

The issue here is that these levels are defined hierarchically (in the sense that each one is accountable to the level above it), as opposed to being defined in terms of the tensions held between them, which look different in terms of rings and wedges:

- Operational Leadership becomes responsible for supply-side leadership of defined services, accountable for the way these services can deliver outcomes in combination with other services[5];

- Front-Line Leadership becomes responsible for demand-side leadership at the edge of the organisation, accountable for the dynamic alignment of combinations of services appropriate to the situation and context of a demand[6];

- Front-line workers become responsible for task leadership, ensuring that a particular alignment of services is delivered effectively; and

- Strategic leadership becomes responsible for asymmetric leadership – leadership which enables the organisation to hold and sustain a dynamic balance between its supply-side and demand-side.[7]

Asymmetric leadership is about enabling dilemmas to be held effectively E-W

The use of hierarchy has to be placed in the context of networked forms of organisation and distributed or collaborative approaches to leadership.[8] Operating within these turbulent complex ecosystems cannot be managed independently of the dynamics in the environment. In the place of hierarchy with its defined outputs as an overarching organising principle therefore comes the containing of dilemmas and a double challenge.[9]

Notes

[1] The difference between North-South and East-West dominant assumptions about governance is introduced here, with comment on the consequences of North-South dominance on the East-West axis here.

[2] A close reading of the detailed content of the framework clearly recognises the issues raised in this blog. The difficulty is that the conceptual scaffolding within which the framework is constructed rests on presumptions of hierarchy. For more on conceptual scaffolding, see Lane, D. A., R. Emilia, et al. (2005). “Ontological uncertainty and innovation.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 15.

[3] For more on this three-way distinction, see creating value in ecosystems: establishing a 3-level approach to strategy.

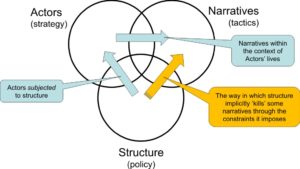

[4] Another way of understanding the relations between policy-strategy-tactics is in terms of the dual span of complexity and associated timespan of discretion, complexity and timespan being synchronic and diachronic ways of describing a system. In these terms the actors within a system are subjected to (i.e. constrained in their choices by) structure; and narrative takes place within the context of actors’ lives. Policy is thus structural in its effects, strategy is about asserting and sustaining difference between actors, and tactics are the unfolding of narrative within this context. A forensic process therefore examines the implicit effects of structure on narrative in order to identify how its constraints ‘kill’ certain kinds of narrative i.e. prevent certain kinds of outcome.

Jaques’ insistence on discrete levels of discretion can be understood in these terms as relations of subjection. The figure above is derived from Figure 5 in Christian Dominique and Stephane Flamant, “Strategic Narrative: around a narrative intervention assisted” French Management Review, 2005/6 No. 159, p. 283-302.

[5] This is referred to as the primary task of the service…

[6] … while this is referred to as the primary risk faced by the particular relation to demand. See quality as the driver at the edge for more about these two axes.

[7] This creates challenges for the organisation, both enabling its client-customers to be related to one-by-one by authorising leadership at the edge, and also by creating appropriately agile supporting platforms and infrastructures that make this sustainable. This kind of complex organisation I refer to as quantum organisation.

[8] For more on the architectural implications of quantum organisation, see architectures that integrate differentiated behaviors

[9] For more on the different nature of complex environments, see the drivers of organisational scope.