by Philip Boxer

In the previous blog I introduced the whole economy of leadership. Here I outline a case showing my diagnostic use of this economy.

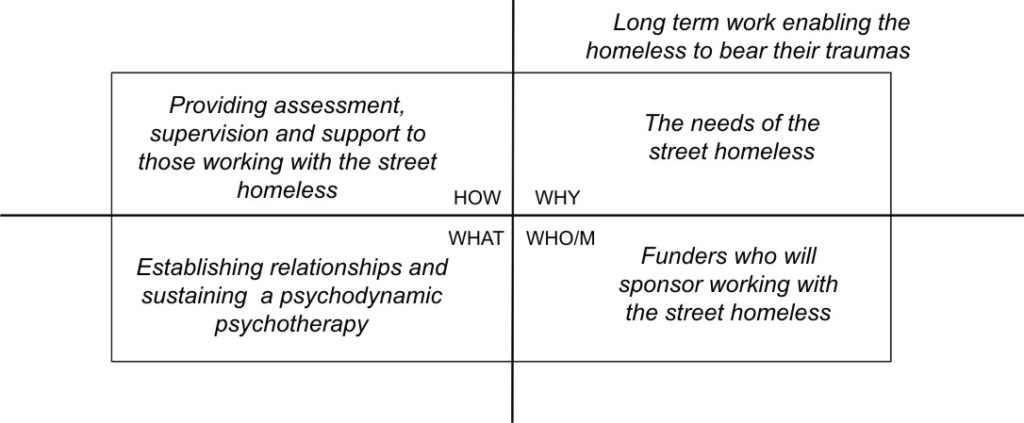

The case is about a non-profit organisation that had developed a model for providing long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy to the street homeless. It was par excellence an edge organisation, providing an organisational platform that sought to align the needs of funders, psychotherapists-in-training, homeless shelters and traumatised individuals. The following describes the four different forms of ‘truth’ within a domain of relevance with which members of the organisation were identified:[1]

The members of the organisation were identified with different aspects of the work of enabling the homeless to bear their traumas through the use of long term psychodynamic psychotherapy. Within this chosen domain,

- Volunteer psychotherapists in training worked with homeless persons for up to 2 years – the ‘WHAT’.

- Management used a model that provided assessment (of need), supervision (of volunteers) and support (to the whole process) – the ‘HOW’.

- Driving all this was the relation to the particular form taken by the needs of the street homeless, for example shaping where and how these needs could be encountered – the ‘WHY’.

- Who the organisation could be for whom was determined by the way funders were prepared to fund its work – the ‘WHO/M’. So what was the problem?

I was a Board member, and the challenge we faced in common with many other non-profits was a change in the way funding was made available, with the attendant changes this demanded in strategy. This case was essentially about a failure of strategy – hence the homelessness.

Previously, funders had been prepared to pay for the whole service as a ‘good thing’ – this was the history that both the Director and the Board were familiar with. But funders were increasingly wanting to link their funding to outcomes related to specific projects. The difficulty was that the needs presented by the homeless were multi-sided, and not easily fitted into simple output measures. To be effective, the work being done had not only to address the homeless person’s direct need, but also to meet their indirect needs by the way the work ‘fitted’ alongside other things being done, for example arranging accommodation and food, managing addictions and addressing health needs. This was not only a complex ‘narrative’ that was difficult to get funded. It also demanded edge-driven collaboration between multiple organisations.

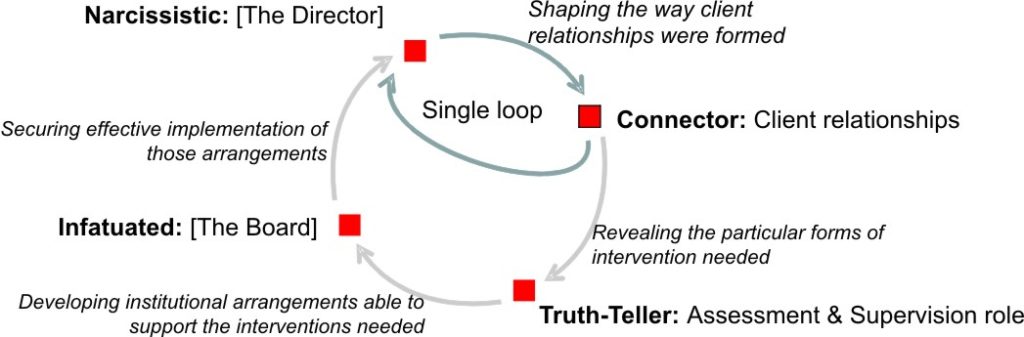

The organisation needed to get funders involved with its work. But to do this, it needed to make its models more dynamically responsive to the multi-sided nature of the needs being presented by the homeless, so that its role within the larger ecosystem could become clearer. In terms of the network-forming leadership roles, this demanded triple-loop learning of the organisation. In practice, however, the attachment of the Director and the Board to old ways of thinking about the service made this impossible, the organisation continuing single-loop behavior under its founding model. It was not able to be strategic:

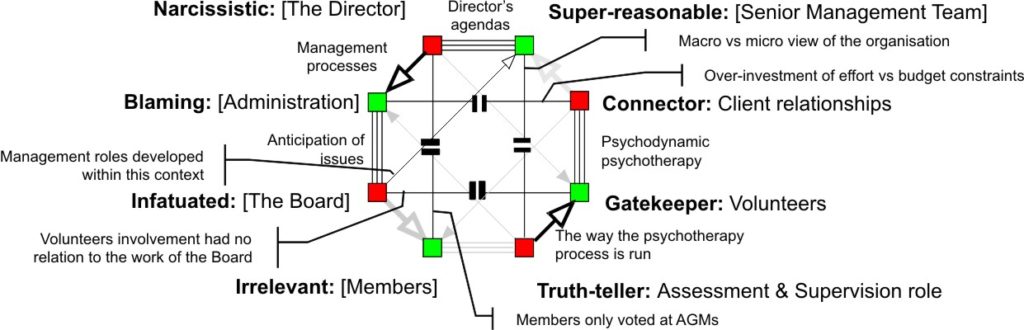

A closer look at the full economy of leadership shows why this was the case. The full economy adds in the network-enabling forms of leadership and the relationships within the economy as a whole, the anti-patterns of leadership being shown in square brackets. It shows how the organisation was split:

- The ‘heart’ of the organisation was in the volunteers’ work with the clients under supervision. For the volunteers this was a valuable extension to their training. ‘Management’, whether in the role of the Senior Management Team (SMT) or by Administrators, belonged to a different kind of agenda, being inimical to the volunteers’ work but suffered by them as necessary to complying with Board requirements. The disconnect between the work with clients and the SMT was symptomatic of this. Equally, the agenda of the volunteers in extending their training had no real relationship to the Board’s view of the organisation.

- The ‘head’ of the organisation was in the work of the Director and her administration supported by the Board, all three of which were more identified with the past ways of doing things than current pressures for change. Given that the allegiance of the SMT was more to working with volunteers than with the Director’s or Board’s agendas, their demands for super-reasonableness reflected their resistance to engaging with the demands for change emerging from the work with clients. The members, who constitutionally elected the Board, were also irrelevant, with no real involvement either with the Board or with the work of the organisation, other than voting at their Annual General Meeting.

So it was a classic case of clinicians working on a Faustian basis, with ‘management’ and ‘Board’ split off and responding to a quite different set of agendas – agendas that nevertheless would ultimately determine the demise of the organisation.

Of course numbers of things were done to try to build positive connections across the economy as a whole [2] in order to try and overcome these difficulties, examples of which were:

- the (w)edge management process, developed to provide a better alignment between the work of the organisation and the way it could be held accountable to funders.

- Board members spending time ‘in the field’ with members of the SMT and volunteers in order to better understand the work of the organisation.

- Research commissioned with Peter Fonagy on the long-term benefits of the work with the homeless, to better inform funders of the nature of the needs being dealt with.

- Alliances built with the other organisations alongside which the work was done, for example St Mungo’s, so that better collaborative alliances could be built, with these other organisations becoming Members.

- A group relations conference design by Barry Palmer enabling the organisation to develop a relationship between its different parts and itself as a whole.

- Research commissioned on the system dynamics between street homelessness and the behavior of the larger social care system, for which homelessness was a symptom, in order to better situate outcome measures within the context of this larger dynamic.

Ultimately, however, attempts to develop an effective relationship to strategy failed, with an attendant failure to create a place for this particular form of long-term work in the minds of the funders.[3] The consequence was that rather than closing the organisation, the Board merged it with a larger not-for-profit within which it’s work could form a part of a larger whole, within which the multi-sidedness of its work could be better addressed.[4] The absence of an effective relationship to strategy continued, however, and the work of the organisation was eventually closed down.

Footnotes

[1] The ‘truth’ of a discourse is an effect of its structure. It is what the speaker subject to the discourse’s structure feels to be ‘true’.

[2] From the perspective of the Board, these demanded consulting interventions. The diagnostic status of the economy of leadership could therefore be thought of as framing the nature of the need for these interventions.

[3] Fundamentally, the anti-patterns on the left side of the economy were never overcome… personally, I never really grasped the extent of (and basis for) the resistance that persisted to the end. In retrospect, using volunteers in the way that it did probaly compounded this by rendering invisible much of the real demands at the edge.

[4] The merger addressed the funding issue by placing the operating model alongside a number of other services, enabling the multi-sidedness of homeless needs to be managed more effectively. The merger was an intervention’ that changed what the organisation identified itself with. But it didn’t change the economy of leadership that persisted into the new organisation.