by Philip Boxer

In the chapter with Richard Veryard on Taking Governance to the Edge, I introduced a model of the WHAT, HOW, FOR WHOM and WHY of the relationship between a business and its environment:

The concept of a governance cycle was based on four different ways in which the supplying ‘inside’ could be related to demands on the ‘outside’, in which the movement around the cycle was driven by standardization or customization of supply and demand models. Thus in the move to ‘comparison’, demand is standardised, in moving to ‘cost’ supply is also standardised, and in taking up a ‘custom’ relation to demand, there is sufficient flexibility in standardised supply model to be able to customise its relation to demand in different contexts:

The names for two of these four ways came from research on shopping behaviour by Gary Davies in which he distinguished ‘cost’ convenience (choosing between similar standardised offerings) and ‘comparison’ behaviours (choosing between different solutions to the same demand). The other two separated out circumstances where there was a demand particular to the customer, distinguishing offerings in which there was only one place for the customer to go ( ‘destination’), or in which the supplier would adapt the offering to the customer’s requirement ( ‘custom’) within their context-of-use. The point being made, however, was that the ‘destination’ form of offering required asymmetric governance because of the need to hold power at the edge of the organisation. What distinguishes this position in the cycle?

If we think of the original development of pc-based spreadsheet programs in-house (destination), they soon became a limited number of alternative branded solutions (comparison) that in turn became dominated by the one offering all the others’ features in one package (cost). From here we have seen an increasing ability to customise the ways it can be used (custom) to the point where we are now looking at a new cycle of web-based solutions that we can build one-by-one (destination).

An answer can be found in Max Boisot’s book on Information and Organisations (HarperCollins 1994) in which he distinguishes two axes, one giving an account of the codification of a domain of knowledge, and the other an account of the diffusion of that knowledge across a population. Four different kinds of knowledge are described by him as a result:

- Public knowledge, such as textbooks and newspapers, which is codified and diffused.

- Proprietary knowledge, such as patents and official secrets, which is codified but not diffused. Here barriers to diffusion have to be set up.

- Personal knowledge, such as biographical knowledge, which is neither codified nor diffused.

- Common sense – i.e. what ‘everybody knows’, which is not codified but widely diffused.

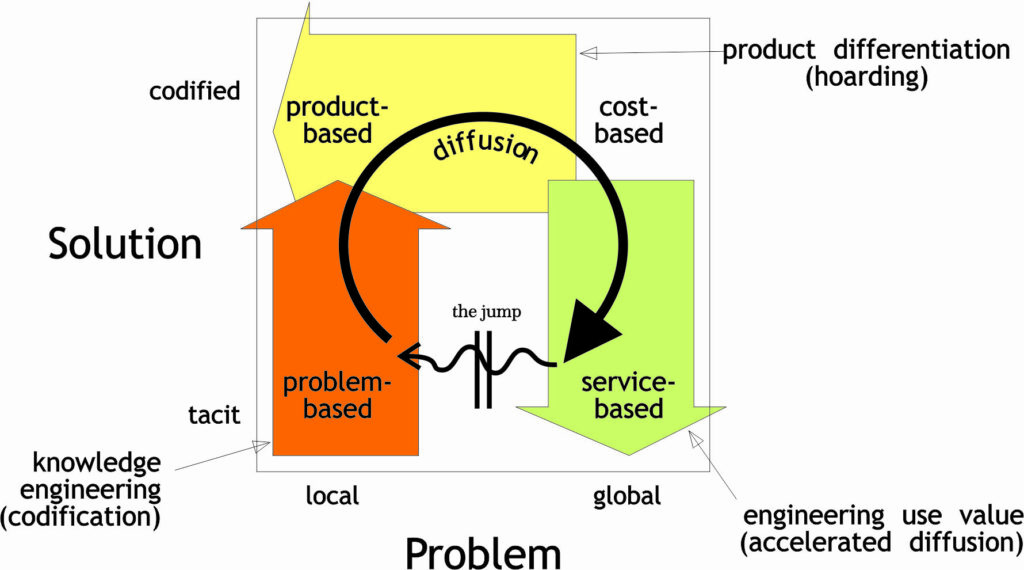

With this comes a knowledge diffusion cycle, which we can approach in the same way as the cycle above, with the ‘solution’ being offered lying along the codification axis, and the customer’s ‘problem’ to which the supplier is offering a solution lying along the diffusion axis:

The result is a cycle showing the initial (problem-based) response as being a personal one to a particular demand in its particular context. A knowledge engineering process of codification can then transform this into a ‘product’, which can remain proprietary for as long as the codification can itself be protected (hoarded). Insofar as it cannot, it becomes public knowledge, so that competition is in terms of the cost of its provision. Finally, the process of embedding this public knowledge back into particular contexts through engineering use value takes us into the ‘custom’ quadrant. From here, the ‘jump’ is about starting a new cycle in relation to a new problem-based response.

It is easy to see in the ‘hoarding’ response a way of describing Microsoft’s defence of its market-leading position. In contrast, the Google approach has sought to accelerate the diffusion and embedding of its technology into others’ mashups to create competing ecosystems (and their associated landscapes) – a strategy of riding the cycle as a whole instead of seeking to hold position within it.1

We see now how it is the personal nature of this problem-based response that distinguishes taking power to the edge of the organisation. It used to be sufficient to rely on the ‘free’ market to incubate such innovations. All business then had to do was to buy the idea, and manage the rest of the governance cycle. The point we make in our paper, however, is that this is becoming more difficult not only because the rest of the cycle is speeding up, but also because demand itself is becoming increasing asymmetric: everyone wanting something different. So in the 21st Century the whole cycle is having to be managed, with the balance between the stages in the cycle changing. This presents those leading at the edge with a double challenge, but it also presents those at the centre with the leadership challenge of developing a capacity for asymmetric governance.

Notes

[1] An interesting example of this is to be found in on of the essays in Platform Economics, called “Two-Sided Markets” by David Evans. To quote from pp145-146:

Two-sided platforms coexist and compete with other business models to fulfill customer needs. Market definition must consider the diverse ways in which a two-sided platform may face rivalry, taking into account the market participants’ reactions to price changes. These reactions are more difficult to predict when the firms are following different business models.

First, a two-sided platform may face single-sided competition on one or both sides. For example, a shopping mall developer faces competition from single stores for the attention of shoppers, as well as from real-estate investors that rent single-store locations. The degree to which these single-sided alternatives constrain the two-sided mall’s conduct is an empirical question.

An example of this is the Microsoft Office Suite competing with the (originally) separately sold word-processing and spreadsheet packages. But now consider Evans’ second type of situation (he goes on further, but these two types serve my purposes here):

Second, a two-sided platform may compete with a three-sided platform. The three-sided rival produces another product which could, for example, have below-cost prices on both sides served by the two-sided platform. A two-sided platform is particularly vulnerable to competition by a three-sided platform that uses its third side to subsidize both of the other sides. This asymmetric competition is potentially lethal to a platform that does not provide the third side. A multi-sided platform can therefore use “envelopment” to challenge platforms that provide a subset of the services it provides. It adds another group of customers to the platform and uses revenues from

this group of customers to lower the price—possibly to zero—of the key profit-generating side of the other platform.

For example, Google gives away office productivity software that competes with Microsoft’s software to users and software developers.44 By doing so, Google attracts customers and profits by selling access to those customers to advertisers. Google can use its advertising revenue

to compete with Microsoft in software. Competition from this advertising-supported software model has led Microsoft to enter into advertising to ensure that it also has a stream of advertising revenue available.

The example here is of Google building targetable traffic by accelerating the diffusion and embedding of the (in this case) office productivity technologies, subsuming Microsoft’s pursuit of direct value by its own pursuit of indirect value. (For more on this distinction, see what distinguishes a platform strategy).