Consultants

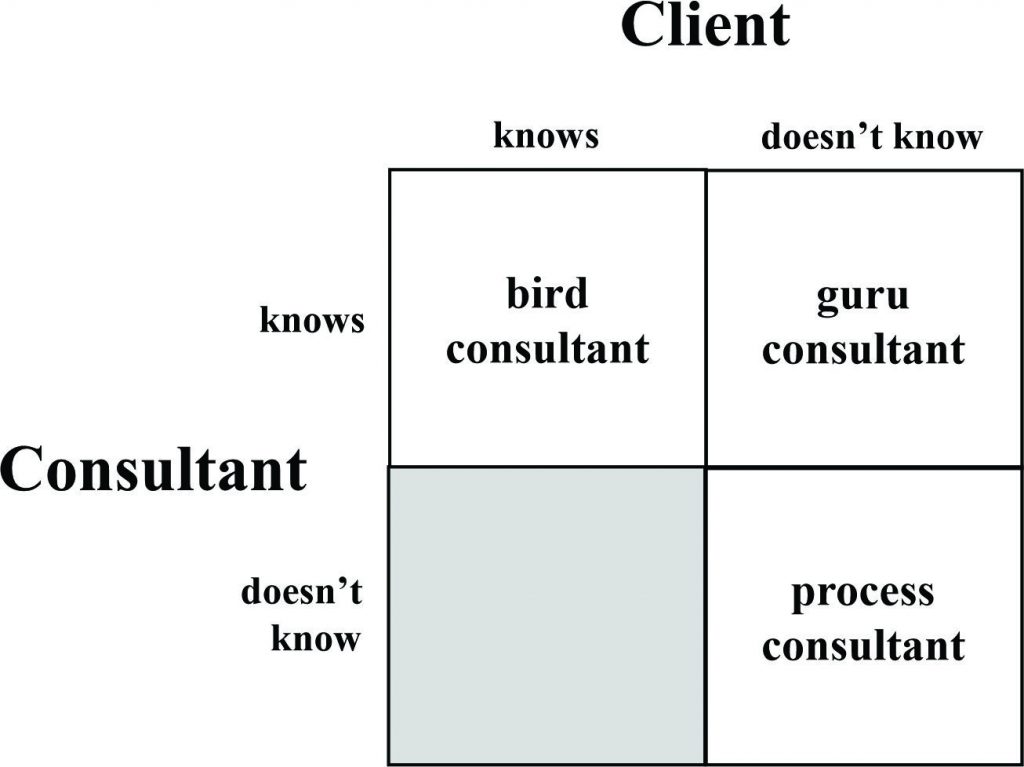

What then do we mean by ‘consultant’? In a recent conversation with Henry Mintzberg[1] he was talking about there being three different kinds of consultant: Birds, Gurus and Process consultants. His explanations of the differences between these three provide a way of approaching the consultant’s way of approaching what is wanting in the business. (Mintzberg incidentally saw himself as a guru).

- Birds picked things up and passed them on to the client. ‘Things’ here were models, techniques, reports etc etc. Most consultants were birds therefore. Provided that the client knew what he wanted, then bird consultants were a very efficient way of getting it.

- Gurus were people who knew a lot, and who could be depended on to come up with explanations for how things were as they were, and how they could be different. Guru consultants could make a lot of sense of things therefore, and were very useful when there was something wrong, but no-one knew exactly what.

- Process consultants finally were people who helped you work things out for yourself. They could be relied upon precisely not to give you answers; and even more not to give you the questions. Mintzberg was interesting on this, in that it was his view that his book on Strategy Process said nothing about the nature of process consulting.

What was in question here was the client’s and the consultant’s knowing. Thus the bird consultant was really an ‘outworker’ – someone whose value to the business was known, and who was brought in in the same way that a sub-contractor might be brought in. Thus the economics of bird consulting depended on his knowledge being something of a commodity.

The difference between the bird and the guru lay in the client’s knowing. Here we have the clue to the “guru” label. The client has a sense that something is wrong but doesn’t know what. But he assumes that someone else does. So he goes where he feels he can place greatest trust in the-one-who-knows. Henry Mintzberg’s track record in research and publications earns him respect as a guru. Clients place their trust in him.

On hearing this, I (of course) reached for my consultant’s 2 x 2 kit and made the following diagram:

The position of the process consultant is paradoxical then. What is this position of not-knowing which the client wishes to share with the consultant? This is the consultant who wants what the client wants, but does not have the answers.

We are looking at a situation in which what is going on is the creation of knowing. It is an understanding of this process of creation which the process consultant brings to the relationship.

Incidentally, the shaded box is also interesting. Part of why clients are cynical about consultants is represented by this box. After the initial meetings with clients in which the contract is made, the lead consultant usually passes on the execution of the contract to assistants/apprentices etc. A quote from Hancock of Kinsley Lord:

“Clients are more sceptical and are reluctant to pay for junior people being sent round. They don’t see why they should pay for the learning curve anymore.” (Hancock 1991)

This shaded box then describes a situation where the client is paying for the consultant to learn on-the-job.

Of course, any consulting assignment involves all four forms of consultancy, but if we take these as ideal forms, then on any particular assignment, we can use them to describe the dominant form.

Case readings

The least that a business case does is to present an aspect of reality. There are usually people, companies, numbers, quotes, narrative, and so on. Thus the case supports a reading of reality, rather than representing reality itself.

I want to borrow from the field of cybernetics, and the distinction made there between 1st order (10) and 2nd order (20) cybernetics. In the beginning was 10 cybernetics[2]. It was 10 because objective science ruled. The assumption built into it was that the way things worked could be wholly explained in terms of their reality.

But the reality was an observed reality, and 20 cybernetics sought to include the role of the observer in the determination of the explanations of how things worked. In 20 cybernetics, the framework of assumptions invoked by the observer ‘brought forth’ the reality observed. In the 20 cybernetics then, language and languaging formed the medium in which and in relation to which reality was formed[3].

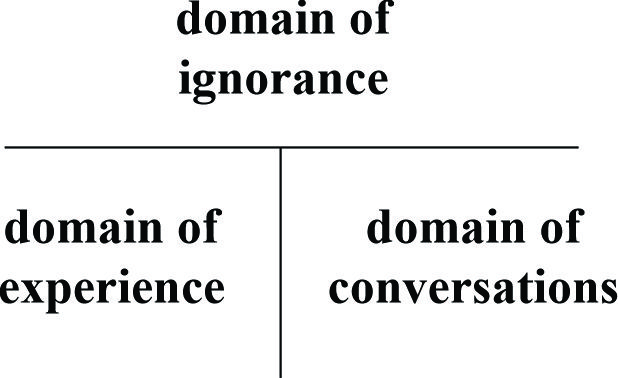

So in 20 cybernetics there were always two non-intersecting domains:

- the domain of conversations; and

- the domain of experience

In the former language and languaging was realised in the form of networks of conversations; and in the latter what was realised was reality.

What has this to do with cases? Consider a 10 reading of a case. In this reading it is as if there is nothing but the reality being presented by the case. In a sense the writing is transparent, so that it is not seen as creating a mediating effect, simply re-presenting reality.

A good case however, which is compelling in its re-presentation of a reality, will lead to a good case discussion, as each participant introduces their reading for discussion. Of course, after some experience of case discussion, the participant soon loses his or her innocence, realising that different participants read different things into the case. But over the course of several case discussions, some degree of consensuality will emerge amongst the participants as to how to ‘read’ the realities presented. We can say that the participants are learning to make 20 readings of the cases together. A 20 reading then is one in which there is an explicit domain of conversations in relation to which the domain of experience ex-ists.

Not all cases however are explicit in their support for a 20 reading. Reading the instructor’s manual for a book of cases, it soon becomes clear that the art in writing the cases is to provoke the 20 effects in the reader rather than to articulate them on the page. But the instructor’s manual elaborates the different possible 20 readings which are likely to come up. Where do we see explicit support for 20 readings? Traditionally in the arts, and nowhere more so than in rhetoric. Wherever we see a particular view being elaborated we have support for a 20 reading.

But what of a 30 reading?

Researchers are used to discussing something called source effect or source bias. They are used to distinguishing between primary and secondary sources. Primary sources are those who have had some form of direct access to the reality of a situation; and secondary sources are those whose knowledge of the reality is acquired through primary sources. A bit like the difference between the evidence of witnesses, and the re-presentation of their evidence by lawyers. But researchers, like lawyers, know that source effect, or source bias, is an inescapable property of any 20 reading, whether by a secondary or primary source: the intent, motive or desire of the source affects the reading.

In recent papers, Vincent Kenny and I argued for a 30 cybernetics.[4] We were arguing that 20 cybernetics made no account of the observer’s existence as such, in just the way that 10 cybernetics made no account of reality’s existence. For the former the observer was ‘just there’ in the same way as reality was ‘just there’ for the latter.

So we sought to construct an account of the presence of the observer, doing so by arguing that the subject is an invention in the place of nothing, and brought about by the structuring effects of the signifier.[5] In this account, the ‘knowing’ of the subject obscures what the subject is wanting: in knowing something, other things are always left out. Which leads us to a third domain – the domain of ignorance – and to the nature of a 30 reading – a reading of the bias or source effect of the 20 reading in terms of what is obscured by it, what is left out, or what is left wanting.

This wanting which is the characteristic of the domain of ignorance is another way of approaching the question of the subject’s intent, motive or desire. When approached in this way, it becomes the subject’s question.

The relation between these three domains can be represented as follows (with apologies to accountants for the allusion to double entry!):

In the 10 reading, it is as if there is only the bottom-right domain; in the 20 reading it is as if there are only the bottom two domains; and in the 30 reading there are the bottom two domains in relation to the domain above.[6] This third domain is, of course, not really a domain – or rather it is paradoxical – because any articulation of ignorance ‘moves’ it into one of the other two domains. So this third domain always has this quality of Otherness.

In working with case material in this way, a distinction can be made between different kinds of case in the extent to which they are written to support different orders of reading:

- 10 cases are typically those written for use in teaching, where their scope for 20 readings by course participants is elaborated in the teaching notes/instructor’s manual. This is the most common kind of case, valuable in developing a sensitivity to the 20.

- 20 cases explicitly refer to the author’s own ways of ‘explaining’ the situations presented in the case. Thus the author’s own 20 reading is accessible in the case itself: the case is self-referential as a piece of writing. These kinds of cases are often found in books, where they are used by the author to elaborate ‘what they mean’ in practice.

- Finally, 30 cases only really arise when the author is actually present, so that his desires and intentions in relation to the case situation become questionable. This 30 case only arises therefore in the context of a ‘live’ presentation of a case. Insofar as the form of such a case presentation becomes an expression of the presenter’s desires and intentions, it becomes reflexive: it becomes an account of its own existence as a piece of writing.

When do we encounter a 30 case then? Good cases, supporting multiple 20 readings seriously held, will raise the questions of who is ‘right’ and what is ‘true’. One response to these questions will be to develop a unifying 20 reading which includes them all. Another is to ‘read’ them as different ways of addressing the domain of ignorance.

The former is the tendency of the guru consultant insofar as he is seeking to give the client a unifying sense of his reality. The latter is more characteristic of the process consultant seeking to make sense of a case in which he is currently engaged: the question of the question will directly affect the way in which he engages with the client. So we tend to encounter 30 when working with a ‘live’ situation, either through some process of supervision of casework, or through the nature of the process of intervention itself.

Clients reading

These three different kinds of reading represent different ways of knowing embodied in different kinds of consulting. What happens when we apply these same forms of knowing to the way the client ‘reads’ the problems and challenges faced by his business?

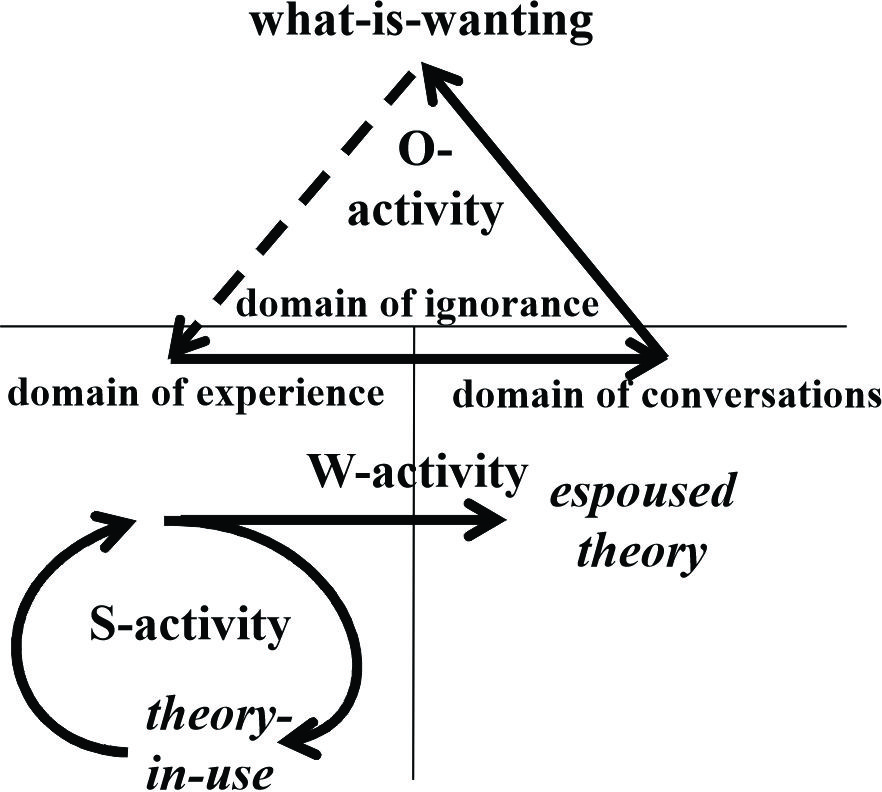

What happens when a client makes a 10 ‘reading’ of a situation in which he finds himself is that it is as if there is nothing but the reality of the situation. His explanations and reasons for doing things are accounts of what is or will be ‘really’ happening.

As consultants, if we were to make a 20 reading of this client’s situation, we would be inclined to observe a theory-in-use even though the client did not articulate it. And were we to make a 30 reading of the client’s situation, we would say that this theory-in-use was consistent with some particular intention or desire which the client held dear. Thus we could say that the client’s ability to achieve his intention or desire was dependent on his theory-in-use – it determined the coherence and continuity of his actions [as an expression of the client’s intention or desire].[7]

But we couldn’t claim that it was the theory-in-use, or even the client’s theory-in-use: only our 20 reading of his actions, and as such an attempt to describe the client’s dependency [aka relation to intention or desire]. These actions however, informed by his 10 reading of his situation, and in which we could say there was a dependency on some theory-in-use, would be S-activity[8]. ‘S’ for sentient. Sentient in the sense of there being nothing but this reality experienced by the client, in which things simply were as they were.

If the client developed a 20 reading of his situation, he would be developing a way of speaking his own theory-in-use. As observers, we might well have a different 20 reading. If we worked at developing an agreed form of it with the client which enabled him to address his reality in such a way as to enable him to manage it to his satisfaction, we would be engaging with him in W-activity. ‘W’ for work.

So W-activity is the work of formulating a 20 reading of a situation by those in the situation. To contrast the form dependency takes when this work has been done, we would say that W-activity transforms extra-dependency to intra-dependency: whereas in S-activity, it is as if the coherence and continuity of his actions are located outside himself in the situation, in W-activity, the client authorises his own theory-in-use as the source of coherence and continuity in his actions.

What then drives this move from S-activity to W-activity? If the form of the client’s dependency is the coherence and continuity of the client’s actions, the client may be driven to W-activity as a response to a breakdown in this coherence and continuity: a loss of coherence and continuity. This will be the external shock which Hancock spoke of in that interview:

“What has focused these troubles is the need for consultancies to concentrate on providing clients with strategies for managing change. It is the biggest challenge for top managements. The hardest problem for managing directors is keeping their companies at the top when they are already very successful and do not have any external shocks to force change.” (Hancock 1991)

In this case W-activity would be a response to ‘breakdown’ as an opportunity for learning[9]. But two other responses would also be possible:

- the ‘breakdown’ may simply be seen as a problem to be fixed; or

- it may be taken as an opportunity for learning, but the learning of someone else’s solution. It is this response to ‘the problem’ which gives rise to espoused theory. Espoused theory is in this sense a solution looking for a problem.

The first of these responses defines the role of the bird consultant; and the second that of the guru.[10] Both leave the client in S-activity, insofar as they remain extra-dependent, albeit, in the second response, explicitly so.

So we have arrived at the point of being able to say something about what the consultant wants. The bird consultant wants to have the answer. The guru consultant wants to engage in W-activity around the problems presented by the client, but as the guru consultant’s W-activity, and not the client’s.

And why not? The cultivation of business’ extra-dependency is good for consultants’ businesses.[11] It is practical for the business too, when no business can afford to invest in knowing about everything. It makes sense to have a strategy which is based on developing only those competencies which it considers to be core.

Managing Networks

So the reason why the client should develop his own 20 reading of his business seems to be in the nature of the process needed for formulating strategy itself. Unless the business develops its own capacity for W-activity it can never claim to be its own master. Its strategies will always be implicit in its history and/or its advisers. This will set a limit on the nature the strategies it can pursue.

There is nothing wrong with using the other two responses – both save a lot of time, by making use of others’ learning. Unless, that is, learning is of the essence. In which case these two responses limit the client’s learning by leaving him the client extra-dependent. These responses ‘fix’ his problem, or ‘patch’ his understanding in ways which will not be connected with his own learning, unless they become incorporated in his own W-activity.[12]

What then is senior management ‘doing’, if it is directing such learning processes in a non-directive way? Part of the answer to this has also been summarised well in a recent Harvard Business Review Article (Charan 1991). In this the author approaches networks as “the small company inside the large company” – the means for building competitive advantage. The membership of a network is based on the unique set of individuals at all levels and across all parts of a company who have between them the capability for generating the learning and change needed. The role for senior management in this strategic use of networks is very informative on what senior management should be ‘doing’:

“Senior managers work as change agents to create a new ‘social architecture’ that becomes the basis of the network. Once the network is in place, they play at least three additional roles. First, they define with clarity and specificity the business outputs they expect of the network and the timeframe in which they expect the network to deliver. Second, they guarantee the visibility and free flow of information to all members of the network and promote simultaneous communication (dialogue) among them. Finally, they develop new criteria and processes for performance evaluation and promotion that emphasise horizontal collaboration through networks. They openly share these performance measurements with all members of the network and adjust them in response to changing circumstances.”

What is being described here is the establishment of a network of conversations which are both conversations for understanding and conversations for action. Senior management is creating the conditions for the existence, support and legitimacy of such networks. We are all familiar with the way informal networks operate in organisations. This is formalising the informal – harnessing its energy to generating learning for the business.

Managing networks can be understood therefore as a way of developing a 20 capability for W-activity in a business, giving the business a capacity for generating change. Where does this place senior managers?

O-activity

The other part of the answer to what senior managers are ‘doing’ in directing non-directively relates to the nature of their own processes. I have argued for the importance of supporting the client’s own process of W-activity[13], which results in the client developing an espoused theory: their strategy. This strategy is their (20) reading of how they wish their business to be, one that must then be realised in the behaviour of the business.[14] This combination of understanding and action is what emerges from managing networks in the way described earlier.

Many businesses have developed their own strategy processes which have enabled them to choose market position on the basis of their competitive strengths. But, unlike the networks approach, which can form a permanent part of the way a business operates, these have tended to be task forces with a temporary existence. This tendency enables the leadership of a business to identify itself with the outcomes of such a task-force process. In this sense the leadership becomes the business’ own guru and task forces the leadership’s private W-activity. By choosing to give comfort to management that they are following the right strategy, in the interests of creating alignment of interests and common direction, the leadership paradoxically sets another kind of limit on the development of new strategies – that which we have seen graphically illustrated in the current demise of the command economy. Unless legitimised by the leadership itself, there is no legitimate basis left for opposition or questioning of strategy. No further need for learning is included.

A 30 reading of this strategy, however, would take it as being in the place of what the business is wanting – and as such is also a way of managing its relation to what is to be ignored. What happens next then seems to depend on two possibilities:

- The business carries on with this strategy until it obviously doesn’t work – i.e. until a breakdown shows itself in the domain of experience in the form of a crisis; or

- The business continues to re-design its strategy by addressing itself to what it has ignored – i.e. by developing a 30 reading of its strategy from which new possibilities can arise.

The first is a step back brought about by a loss of coherence and continuity. The second is a step forward in the sense of being about creating a new form of coherence and continuity. It is this second possibility which is O-activity[15]. ‘O’ for Other, and ‘O’ for oscillation[16].

O-activity as Other-activity implies a way of working where there is an active interrogation of what is being ignored – the 30 reading. This form of reading does not constitute a domain in the same way that the other two domains can be said to exist as experience and conversation. Rather it is a direction which emerges through the way the business works in relation to this Otherness with its lack. This direction is the continuous pursuit of quality in the strategy itself[17].

O-activity is read as Oscillation-activity because such activity inevitably means moving back-and-forth between positions of intra-dependency and extra-dependency as new questions suggest new forms of activity which themselves suggest new forms of meaning, and so on. Instead of being forced back into extra-dependency by breakdown therefore, with all its implications for the choice of new leaders and new ‘big ideas’, oscillation assumes this movement through choice in order to learn more about the possibilities for action.

O-activity is an approach to managing (to) change which does not rely on external shock to force change. As an alternative to depending on crisis, it is not quite like ‘managing’ in the normal sense of the word. Rather it is a particular quality of relation to strategy which assumes it never to be complete: a commitment to a continuous process of learning which, while never stopping, has direction.

Stopping learning leads to prescriptions. The direction of O-activity takes the form of a continuous questioning of performance.[18]

So a leadership committed to O-activity in relation to its businesses is also a leadership committed to developing a business’ capacity for change. It is this O-activity which enables a constant development of a business’ competencies, and a constant search for new ways of deploying them in the creation of value.

Notes

[1] This was in the context of a series of workshops run by Professor Barwise of the London Business School, in which we were using his book ‘The Strategy Process’ (Mintzberg and Quinn 1991) as a source book.

[2] Cybernetics was founded as such by Norbert Weiner in a book by that name published in 1948 (Weiner 1948). and elaborated in non-technical terms two years later in The Human use of Human Beings (Weiner 1954). As is so often the case, Weiner’s conception of cybernetics was as an extension and elaboration of the human, and not the inversion of this through which cybernetics is popularly known as the encroachment on the human by the mechanistic.

[3] An excellent positioning of 20 cybernetics in relation to the processes of change is in Vincent Kenny’s special issue of The Irish Journal of Psychology entitled Radical Constructivism, Autopoiesis and Psychotherapy (Kenny 1988). It is devoted to new presentations, by some of the leading authorities in the field, on the current epistemological stance of radical constructivism; and is informed by a cybernetic and systems orientation, and the need to redefine the ‘knower’ as a consensual observer-community.

[4] The economy of discourses: a third order cybernetics (Boxer and Kenny 1990); and Lacan and Maturana: constructivist origins for a 30 Cybernetics (Boxer and Kenny 1992).

[5] This ‘structuring effects of the signifier’ is a coded way of referring to a Lacanian view of the subject. See for example Lacan and the subject of language edited by E. Ragland-Sullivan and M. Bracher (Ragland-Sullivan and Bracher 1991). For Lacan, the subject is an invention in the place of a lack, formed by the structuring effects of language. At the heart of language is the function of ‘the signifier’, which is that which marks a difference in relation to another signifier.

[6] A way of elaborating this approach to ‘reading’ using case material makes use of a technology called Critik. This technology supports a reflective analysis of the case material in such a way as to articulate the different orders of reading. The technology is used to help its user to see the patterns in how they use language to pattern difference.

[7] Theory-in-use and espoused theory are terms Argyris and Schon coined to distinguish between what actually governed a person’s actions from what that person said governed his actions (Argyris and Schon 1974).

[8] This and the subsequent W-activity is a re-working of the formulation of S- and W-activity by Barry Palmer and Bruce Reed of the Grubb Institute, which was itself founded on Bion’s concept of basic assumption activity and workgroup activity.

[9] Reg Revans’ Action Learning is of course precisely a way of organising this response.

[10] These are references to the distinction between ‘bird’ and ‘guru’ consulting in (Boxer and Palmer 1994).

[11] This dilemma facing the professional was elaborated by Donald Schon in his book The Reflective Practitioner (Schon 1983). In this he points out the difference between the forms of knowledge to which institutions appear committed (academia), and the professional’s knowledge-in-action. He calls for reflection-in-action as an essential means by which the professional practitioner can make his practice questionable not only to himself, but to his clients. Of course this leaves open the question of whether it is in the professional’s interests to make his practice questionable.

[12] Illich spoke of the difference between disabling and enabling professionals, depending on whether or not the professional had a long-term interest in developing the capability of the client for effective action, or in fostering an extra-dependency on his advice(Illich et al. 1977). Here I am suggesting that ‘fixing’ and ‘patching’ are inherently disabling learning processes if not part of a client’s W-activity, which is not to say that they cannot be justified in terms of results. This “if they are not part of the client’s W-activity” means that the client must be managing the learning process for himself.

[13] An example of this way of working is the use of strategy process made by Harold Kelner and Associates. This approach works with internal teams of managers, and makes use of workbooks to give a shape to their W-activity. The workbooks determine the form of the work activity, and are themselves designed around the needs of the client.

[14] Such ‘realising’ involves not just addressing how people behave, but also how the architectures of the supporting systems are designed, raising the whole question of their over- and under-determining effects on people’s behaviour. I had begun to write about these architectural issues in (Boxer 1979b) and (Boxer 1979a). I didn’t fully address them, however, until much later in (Boxer 2012)

[15] O-activity is in acknowledgement of Bion’s ‘O’ position, although not based on it. Bion’s ‘O’ emphasised the radical Otherness of this ‘position’, in this sense formulating it more as a direction than a position. Whereas for Bion, it involved a being in relation to a (Platonic) ideal form which was also a plenitude (‘O’ for omniscience), here we follow a Lacanian reading that implies a being in relation to that which is lacking in the Other.

[16] Bruce Reed originally formulated the concept of oscillation as a way of speaking about the dynamics of religious process (Reed 1978). This formulation makes a distinction between religious process and religious movement – particular ways of organising religious experience; and refers back to the roots of the word religion in re-ligare – to bind again or bind back. Thus this oscillation was a way of building meaning back out of experience.

[17] I later wrote about this relation to ‘lack’ in a paper on the dilemmas of ignorance (Boxer 1999) in which it becomes the relation to a third dilemma of ‘affiliation versus alliance’ or, in Foucault’s terms, the retreat and return of the origin (Dreyfus and Rabinow 1983).

[18] A continuous questioning, therefore, that, in bringing about learning, changes the basis of performativity in Austen’s sense: (Austin 1962)

References

Argyris, Chris, and Donald A. Schon. 1974. Theory-in-Practice: increasing professional effectiveness (Jossey-Bass: San Francisco).

Austin, J.L. 1962. How to do things with words (Oxford University Press: Oxford).

Boxer, P.J. 1979a. ‘Designing Simulators for Strategic Managers’, Journal of Management Studies, 16: 30-44.

———. 1979b. “Managing Metamorphosis.” In 25th International Meeting of the Society of General Systems Research, 296-305. London: Springer-Verlag.

———. 1991. “What does a Consultant want?” In. www.brl.com: Boxer Research Ltd.

———. 1999. ‘The dilemmas of ignorance.’ in Chris Oakley (ed.), What is a Group? A fresh look at theory in practice (Rebus Press: London).

———. 2012. The Architecture of Agility: Modeling the relation to Indirect Value within Ecosystems (Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany).

Boxer, P.J., and J.V. Kenny. 1990. ‘The economy of discourses: a third order cybernetics?’, Human Systems Management, 9: 205-24.

———. 1992. ‘Lacan and Maturana: Constructivist Origins for a 3rd order Cybernetics’, Communication and Cognition, 25: 73-100.

Boxer, P.J., and B. Palmer. 1994. ‘Meeting the Challenge of the Case: the Place of the Consultant.’ in R. Casemore, G. Dyos, A. Eden, K. Kellner, J. McAuley and S. Moss (eds.), What makes consultancy work – understanding the dynamics (South bank University Press).

Charan, R. 1991. ‘How Networks Reshape Organisations – for results’, Harvard Business Review, Sept-Oct: 104-15.

Dreyfus, H.L., and P. Rabinow. 1983. Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics 2nd Edition (University of Chicago Press).

Hancock, Ian. 1991. “No supermarkets for Hancock anymore.” In, edited by Robert Bruce, 30-31. Management Consultancy.

Illich, Ivan, Irving Kenneth Zola, John McKnight, Jonathan Caplan, and Harley Shaiken. 1977. Disabling Professions (Marion Boyars: New York & London).

Kenny, J.V. 1988. ‘Radical Constructivism, Autopoiesis and Psychotherapy’, The Irish Journal of Psychology, 9.

Mintzberg, Henry, and James Brian Quinn. 1991. The Strategy Process: Concepts, Context, Cases (Prentice-Hall).

Ragland-Sullivan, Ellie, and Mark Bracher. 1991. Lacan and the subject of language (Routledge: New York and London).

Reed, B. 1978. The Dynamics of Religion: Process and Movement in Christian Churches (Longman & Todd: London).

Schon, Donald A. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner (Basic Books).

Weiner, Norbert. 1948. Cybernetics (MIT Press: Cambridge, MA).

———. 1954. The Human Use of Human Beings (Houghton Mifflin).