If we take up the biological metaphors from the 2nd blog, we must consider how to set aside the vertical cybernetic approach to sovereignty, based on an external authority, in order to approach a structural ecosystem as being like a holobiont in which adaptation becomes a general property of structural ecosystem understood as a living system. This will involve considering its constituent organizations, business units, subcontractors and outsourced services as also able to be understood as living systems. For convenience, we will refer to all of these as symbionts. The structural ecosystem qua holobiont will be defined in terms of the structural coupling described in the blog on agency between its symbionts and their environments. This restricts the definition of a superorganism as a social organization of corporations qua vertically-defined symbionts subject to external sovereignty. As a living system, the governance of a symbiont will be approached in terms of the way it exhibits agency through one of the four different types of behavioral strategy identified in the 3rd blog (archaea, protobiota,[1] bacteria and eukaryota).

“… the ‘fundamental’ life types are the parsimonious realizations or prototypes of autopoietic systems … There are four primary types with constructive subtypes that lead to M-R closure by combining into hybrid forms. Clearly, all complex evolved life forms are hybrids of the fundamental types, just as hybrids of incomplete forms may explain the origin of the fundamental types: how organismic life evolved from proto-life. … (Kineman 2018)

As we shall see, this will involve identifying the four types of behavioral strategy with four different types of value proposition.

The three consistencies of a symbiont

We start from the understanding established in the 4th blog that the behaviors of a symbiont necessarily involve holding three consistencies in relation to each other in the sense of a borromean knotting:

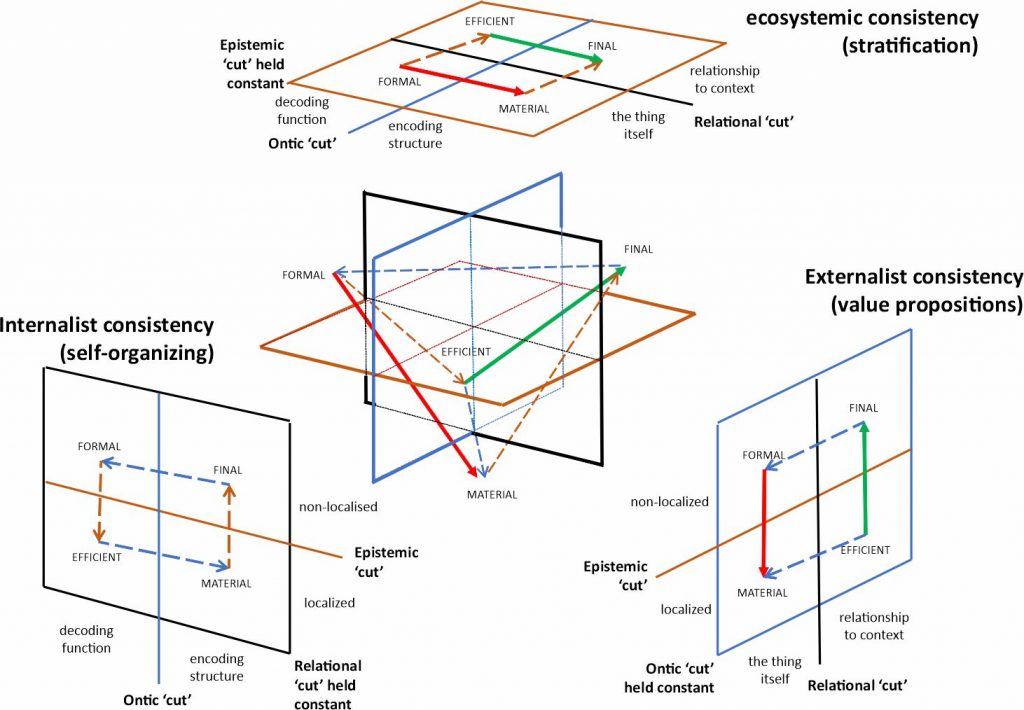

Figure 1: The three consistencies of a holobiont.

- How its identity is defined – the internalist consistency defining a self-organization of the relation to what the environment is understood as ‘wanting’, established by holding the relational ‘cut’ constant. This captures the circular causality of the symbiont through which its identity is defined on the basis of a static definition of its relation to its environment. The circular relations between the material, efficient, formal and final causes capture how this relation to its environment is sustained. [2].

- What it can do for its environment – the externalist consistency defined in terms of the different kinds of value proposition that can be offered by a symbiont, established by holding the ontic ‘cut’ constant that defines what a symbiont can ‘do’. These value propositions are the different types of behavioral strategy described below. This consistency shows the dependency of the symbiont’s efficient-cause Operations on its material-cause Capabilities constrained by its final-cause Strategy and its formal-cause Organization.[3]

- What its place is within the larger ecosystem of which it is a part – the ecosystemic consistency of the stratified relation of the symbiont’s capabilities related to ultimate customers and supported by underlying capabilities, established by holding the epistemic ‘cut’ constant. This shows the dependency of the symbiont’s formal-cause Organization on its final-cause Strategy , constrained by its efficient-cause Operations and its material-cause Capabilities.[4] This consistency, shown in Figure 3, is like a fractal showing the stratified relations between its constituent parts. The stratification is in the way underlying capabilities are made available, in the way products and services are aligned, orchestrated and made to cohere, and ultimately in the way customers value the direct and indirect effects of supply-side behaviors within their contexts-of-use. The stratification arises from the way each of the layers builds on the previous layer, Figure 2 describing the way behavioral strategies support behavioral strategies support customers’ contexts-of-use. The relations between the causes in this consistency provide support for cultural immune systems[5] rooted in the way behavioral strategies support different kinds of ‘truth’ in the identifications of the individuals involved.

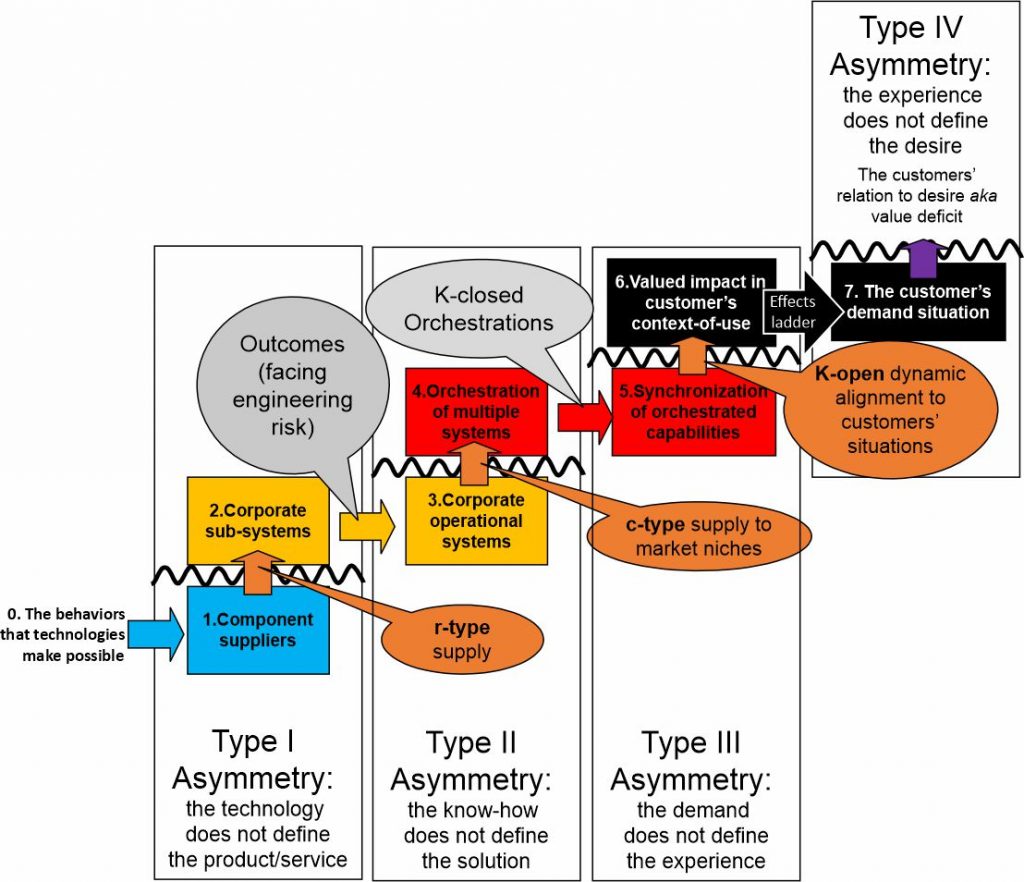

This ecosystemic consistency, based on holding the epistemic ‘cut’ constant, views a living system in terms of three asymmetries with respect to the framing domain of relevance implicit in its epistemic ‘cut’:

- 1st asymmetry: the underlying technology does not define the product/service.

- 2nd asymmetry: the supplier’s know-how does not define the solutions offered the customer.

- 3rd asymmetry: the customer’s demand does not define what the customer wants to experience.

An ecosystemic understanding of a holobiont may thus be described by the way these three asymmetries are held in relation to each other. Figure 2: The ecosystemic consistency of stratification relating underlying technologies to ultimate demands.

Figure 2: The ecosystemic consistency of stratification relating underlying technologies to ultimate demands.

We are using the biological metaphor of living systems, however, to think about adaptation to customers’ changing contexts-of-use as a general property. There is therefore a fourth asymmetry implicit in the formation of a symbiont that must be held in order to be able to adapt to the dynamics in customers’ changing contexts-of-use. It is holding this fourth asymmetry open that becomes critical in turbulent environments. It is between the experiences that are being provided by the symbiont within its customers’ contexts-of-use and the dynamics driving change within those contexts-of-use themselves. This fourth asymmetry falls outside the stratification as it stands because it challenges the domain of relevance aka epistemic ‘cut’ implicit in the way the stratification itself is defined:

- 4th asymmetry: the customer’s experience does not define the customer’s desire, lack or value deficit.

These four asymmetries are shown in Figure 2 as horizontal squiggly lines, each corresponding to a different form of behavioral strategy. The next step is therefore to describe the different kinds of behavioral strategy, identified in Figure 4 of the 3rd blog.

Describing the four types of behavioral strategy

Rosen used to refer to a living system with a given relation to its environment that had been selected by its environment and that engaged in three processes of replication, metabolism and repair (Rosen 1991: p251):

- Replication of its phenotypic way of behaving in its environment,

- Metabolism as its way of of realizing an organization (negentropy) of its constituents[6], and

- Repair as its maintaining of its phenotypic way of organizing its metabolic processes.

For our purposes in order to address the fourth asymmetry, we need to make genotypic selection itself to be a dynamic process:

- Selection of its genotypic way of being in relation to its environment.

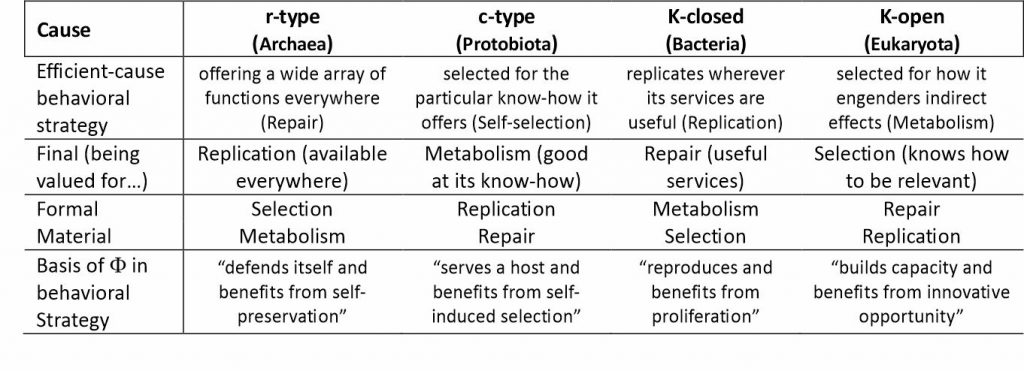

To do this, we apply all four concepts of selection, replication, metabolism and repair to a symbiont, extending the use of to refer to a living system’s whole way of competing. The resultant four kinds of efficient-cause behavioral strategy, paralleling those described in the 3rd blog, each provide a distinct behavioral basis for competing. At the same time, each behavioral strategy can be associated with a distinct final-cause way of being valued (selected) by its environment. These four behavioral strategies with their associated ways of being valued define four kinds of value proposition:

- r-type repair (archaea), based on the task behaviors it provides, replicating a selected way of being useful.

- c-type customization (protobiota), based on being selected for its specialist know-how applying particular metabolic effects. Because of the dependence of this behavioral strategy on the way its host environment uses its know-how, it has two forms, depending on whether the relation to the host is symbiotic or not (not = invasive).

- K-closed orchestration (bacteria), replicating behaviors at its boundaries in closed context-independent or open context specific ways that provide useful repairs in its environment.

- K-open problem-solving (eukaryota), based on being selected by its environment through its ability to engender indirect metabolic effects on ‘problems’ (or ‘pains’) in its larger environment.

The different relations between the four processes for each type of behavioral strategy are summarized in Table 1 along with a characterization of the way they are valued by their environments:

Table 1: The four different behavioral strategies for being valued[7].

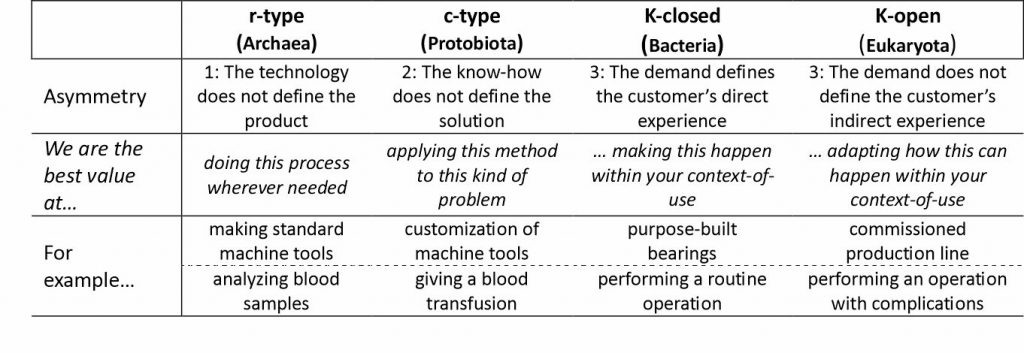

Each of these behavioral strategies relates to the asymmetries in Figure 2 within the context of the stratification as a whole. Table 2 summarises these relations and adds some examples from the machine tool and health care ‘industries’ for illustration purposes:

Table 2: The four different strategies placed within the context of an architectural stratification

The stratified relationships between the four strategies

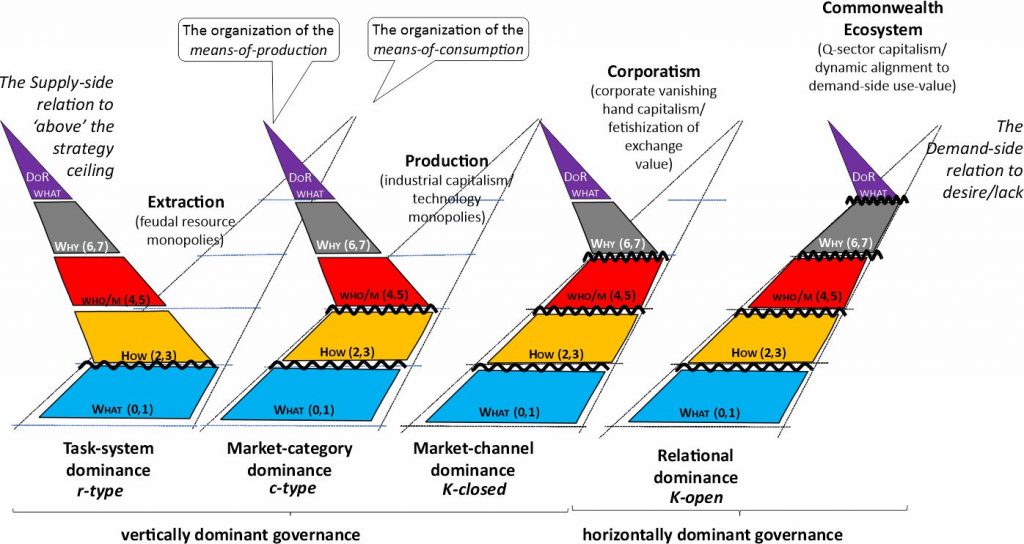

Each of the four kinds of behavioral strategy correspond to a fundamental type of living system. The ecosystemic consistency brings them all in relation to each other for a given domain of relevance (DoR) qua epistemic ‘cut’. Figure 3 identifies this given DoR of the supplier pointing up-left supplying customers’ contexts-of-use, the DoRs of which point up-right.

The r-type proposition on the left of Figure 3 shows the implicit ‘how’ capabilities of a supplier determining ‘what’ is supplied to the customer. The figures (0,1) and (2,3) refer to the layers of the stratification shown in Figure 2. Next is shown a c-type proposition with its implicit ‘who-for-whom’ market definition determining ‘how’ it is useful, the assumption in Figure VI-17 being that r-type products and services are supporting the c-type proposition. Next comes the K-closed proposition with its implicit ‘why’ assumptions about the customer’s context-of-use. Finally, with the K-open proposition, the difference between supplier and customer is solely in the definition of the domain of relevance (DoR).

Figure 3 is showing all four types alongside each other as a progression on the supply-side as the whole role of suppliers within an ecosystem do more and more for customers within their contexts-of-use. The different value propositions don’t all have to be symbionts within the same holobiont, this depending on the governance of the structural ecosystem as a whole.

Figure 4: The stratified relations between the different types of behavioral strategy

Thus,

- In the r-type case, the value for the customer is in ‘offering a wide array of functions everywhere, replicating as much as possible’.

- In the c-type case, the value is in the ‘selection for the particular metabolistic know-how it offers’.

- In the K-closed case, the value is in ‘the ways in which useful services (repair) are replicated within customers’ contexts-of-use.

- In the K-open case, the value is in the provider being selected because of ‘the way it is able to engender indirect effects’ within a customer’s context-of-use.

It remains for the customers to organize how they ‘use’ these different types of value proposition. While they describe different ways of organizing the means of production, their customers may be either other symbionts or ultimate end-user citizens whose means of consumption are organized not around profit but around well-being.[8]

And so to strategy ceilings

Viewing each of the different types of value proposition in terms of the ecosystemic stratification consistency in Figure 2, the externally sovereign governance of an r-type proposition need only make the ‘what’ behaviors responsive to customers. In the case of a c-type proposition, this extends to making the ‘how’ behaviors responsive, for the K-closed proposition making the ‘who/m’ behaviors responsive, and for the K-open proposition making the ‘why’ behaviors responsive. In each case, the supplier’s domain of relevance (DoR) aka its epistemic ‘cut’ will constrain what forms of demand it can recognize and which strata can remain implicit in the way the supplier’s DoR is defined.

It follows that only in the K-open proposition will the provider necessarily be structurally coupled to the dynamics of the customer’s context-of-use. This requires governance to be horizontally dominant, driven from its edges by its dynamic relation to the customer’s context-of-use. It is this need for horizontal dominance that requires some degree of surrendered sovereignty. In all the other types of proposition, the affiliation can be to a supply-side definition of what is to be provided that can remain independent of the individual customer’s situation, i.e., able to be defined in terms of a market. It is the addition of the K-open proposition that requires adaptation to become a general property of a symbiont.

Where the governance of a symbiont is based on vertical authority external to it, therefore, the response to an employee questioning these implicit strata can be that ‘it’s none of your business’. In contrast, for adaptation to become a general property of a symbiont enabling it to become edge-driven, the definition of the DoR and the strategy ceiling itself therefore have to be derived directly from the way value is being created for customers within their contexts-of-use.[10]

In conclusion

There may thus be r-type propositions within a holobiont offering a c-type proposition, and both r-type and c-type propositions may be symbionts within a holobiont offering a K-closed proposition. Particular challenges arise for a holobiont offering K-open propositions, however, as for example in the case of providing intensive social care to individuals (Boxer 2017a) or providing through-life capabilities for supporting a fielded military (Whittall and Boxer 2009). These challenges arise from the tension that has to be managed between the horizontally-dominant governance of the K-open propositions and the existence of vertically-dominant external governance of the other kinds of proposition within the structural ecosystem qua holobiont (Boxer 2007).

The social organization of the relations between symbionts subject to external sovereignty within a holobiont becomes challenging, therefore, when all four forms of proposition have to be dynamically balanced in relation to each other and to the contexts-of-use of their ultimate customers, for example where the effects of digitalization are leading to more and more of demand in the economy being driven from the Q-sectors.[10] This raises the question of what changes this requires of the governing mentalities needed all the way up to the changes required at the level of the changing nature of a nation state’s concerns for its citizens. This will be the focus of the last blog in this series.

Notes

[1] “This quasi-organic form is a ‘self-selection strategist’ that includes various semi-organismic life forms such as viruses, internal organs, and various ecosystemic or symbiotic relations. … We can label it Protobiota in agreement with a previous taxonomic proposal for prototypical life (Hsen-Hsu 1965).” (Kineman 2018)

[2] It is this internalist consistency that lends itself to a vertical cybernetic understanding on the basis of the third order of behavioral closure described in the triple articulation blog (i.e., the formal cause), experienced by the 1st and 2nd order socio-technical systems as sovereign, demanding affiliation through what is experienced as a strategy ceiling determined externally from ‘above’. ‘Affiliation’ here refers to the ways in which individuals’ obedience is bound to the ‘way of doing things’ defined by a vertically- and externally-defined sovereignty understood in cybernetic terms. Affiliation describes how an individual holds the second dilemma of espoused theory versus the unthought known (Boxer 1999).

[3] The relations between the four causes in each of the three consistencies follow the directions of the arrows in Figure 5 of the 4th blog.

[4] This stratification places the corporation’s particular behaviors within the context of the larger ecosystems in which it is competing, relating them to the ultimate contexts-of-use that are being supported by those ecosystems (Boxer 2012; Boxer et al. 2008). This stratification describes the relationships between supply-side and demand-side use-values, see ‘How does 21st century capitalism differ from 20th century capitalism?’.

[5] It is important to consider the libidinal investment that individuals make in the behaviors expected of them by their roles, behaviors that support their identifications, for example in how an individual holds the tension between normative and ‘edge’ understandings of their role as per the previous blog. These identifications lock in particular patterns of relation between individuals that act systemically like a cultural immune system constraining what forms of change can be tolerated by the corporation. Elaborating on what ‘cultural immune system’ means is beyond the scope of this blog, requiring us to go into a Lacanian understanding of the nature of the generative and perverse discourses (Boxer and Kenny 1990). Understanding the dynamics of this immune system as a libidinal economy of discourses (Boxer and Kenny 1992) becomes necessary if the forms of counter-resistance to genotypic adaptation are to be overcome (Boxer 2021, 2014a, 2004). For the purposes of this blog, the metaphor of biological immune systems as per (Schneider 2021) and (Rosen 1974) will be used, as for example in (Hagel III 2017).

[6] ‘Realized’ is used here to emphasize that what is created is an embodied form, not simply a more complex design for realization. See (Moreno-Bergareche and Ruia-Mirazo 1999)

[7] Quotes from (Kineman 2018)

[8] For the significance of this distinction between producers, consumers and citizens, see ‘How does 21st century capitalism differ from 20th century capitalism’.

[9] The immune system of a corporation is characterized by the DoR assumptions that remain implicit above the ceiling, forming a governing mentality framing the way authority may be exercised.

[10] These are the fourth quaternary (knowledge-based) and fifth quinary (turn-key) sectors of the national economy in which corporations’ behaviors are driven by the needs of individual customers’ contexts-of-use. See ‘The dialectics implied by the Q-sectors’.

References

Boxer, P.J. 1999. ‘The dilemmas of ignorance.’ in Chris Oakley (ed.), What is a Group? A fresh look at theory in practice (Rebus Press: London).

———. 2004. ‘Facing Facts: what is the good of change?’, Journal of Psycho-Social Studies, 3(1): 20-46.

———. 2007. “The Double Challenge in Engineering Complex Systems of Systems.” In AsymmetricDesign. www.asymmetricdesign.com.

———. 2012. The Architecture of Agility: Modeling the relation to Indirect Value within Ecosystems (Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany).

———. 2014a. ‘Defences against innovation: the conservation of vagueness.’ in D. Armstrong and M. Rustin (eds.), Defences Against Anxiety: Explorations in a Paradigm (Karnac: London).

———. 2014b. ‘Leading Organisations Without Boundaries: ‘Quantum’ Organisation and the Work of Making Meaning’, Organizational and Social Dynamics, 14: 130-53.

———. 2017. ‘Caring Beyond Reason: A question of ethics’, Socioanalysis, 19: 34-50.

———. 2021. “Working Beyond The Pale: when doesn’t it become an insurgency?” In ISPSO Annual Conference. Berlin.

Boxer, P.J., and J.V. Kenny. 1990. ‘The economy of discourses: a third order cybernetics?’, Human Systems Management, 9: 205-24.

———. 1992. ‘Lacan and Maturana: Constructivist Origins for a 3rd order Cybernetics’, Communication and Cognition, 25: 73-100.

Boxer, P.J., Edwin Morris, William Anderson, and Bernard Cohen. 2008. “Systems-of-Systems Engineering and the Pragmatics of Demand.” In Second International Systems Conference, 1-7. Montreal, Que.: IEEE.

Hagel III, John. 2017. “Never Under-Estimate the Immune System.” In Edge Perspectives. http://edgeperspectives.typepad.com/edge_perspectives/2017/12/never-under-estimate-the-immunesystem.html.

Kineman, John J. 2018. ‘Four Kinds of Anticipatory (M-R) Life and a Definition of Sustainability.’ in R. Poli (ed.), Handbook of Anticipation (Springer Nature: Switzerland).

Moreno-Bergareche, Alvaro, and Kepa Ruia-Mirazo. 1999. ‘Metabolism and the problem of its universalization’, Biosystems, 49: 45-61.

Rosen, R. 1974. “On Biological Systems as Paradigms for Adaptation.” In The Political, Social, Educational and Policy Implications of Structuralisms. Adaptive Economic Models.

———. 1991. Life Itself (Columbia University Press: New York).

Schneider, Tamar. 2021. ‘The holobiont self: understanding immunity in context’, History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, 43.

Whittall, Nicholas J, and P.J. Boxer. 2009. ‘Agility and Value for Defence’, RUSI Defence Systems: 19-20.