Introduction

We return now to the issues raised by the first blog in this series: what is involved in the doubling of the Harold Bridger’s double task (Bridger 1990)?[1] In order to compete effectively in turbulent environments, a corporation must be able to surrender sovereignty in the way it relates to its customers’ contexts-of-use. This surrendering of sovereignty over the red box in Figure 1 is necessary if the way in which the corporation creates and captures value in relation to any one customer’s context-of-use has to be particular to that customer relationship (Boxer 2014), i.e., to the black box in Figure 1. This faces the person(s) directly responsible for that relationship with a doubling of their double task(s), a doubling in which they must be able both to create the organizational context within which value can be both created and captured for that customer, and to be able also to then execute the roles defined by that organizational context. The challenge presented by these turbulent environments is that this doubling of double tasks has to be scaled across the multiple customer relationships of a corporation.

Figure 1: Responding to turbulence by doubling the double task

An example of this challenge arises where the safety of the customer is of concern in the clinical relationships supported by a healthcare system. ‘Safety I’ can be defined as the absence of failure to follow existing policies and practices according to normative role definitions aka ‘doing things right’ according to the red box in Figure 1. ‘Safety I’ may thus be provided by the deterministic closures delivered by the cybernetic vertical approach to an organization’s behaviors. Suzette Woodward distinguished this from ‘Safety II’, defined as “the ability to succeed under varying conditions so that the number of intended and acceptable outcomes is as high as possible” (Woodward 2020: p43) aka ‘doing the right thing’ in relation to the black box in Figure 1.[2] Safety II includes the double task considerations of Safety I, but requires the role to be understood as an edge role in which there is a doubling of these double task considerations: the Safety I considerations have to be derived from how Safety II is to be achieved.[3]

The previous four blogs[4] have been exploring why socio-technical open-systems thinking with its cybernetic vertical approach is not sufficient for making sense of what it means to ‘surrender sovereignty’ in this doubling of the double task. The blogs have argued that corporations facing a turbulent environment must instead be thought of as living systems in which adaptation becomes a general property of the corporation. For this to be possible, a corporation has to develop ‘edge role’ capabilities. This blog explores what this means and what kind of challenge ‘edge roles’ present, a challenge to the relationship to governance as an external vertical authority.

Corporations as symbionts qua living systems

The distinguishing characteristic of symbionts is their ability to take up being in relation to three ‘cuts’:

- An ontic ‘cut’ between the technologies available to a symbiont and the uses to which those technologies can be put in its products and services.

- An epistemic ‘cut’ between the way the symbiont is organized and the way it organizes solutions that can be made available to its customers.

- A relational ‘cut’ between the way the symbiont defines solutions and the way customers actually experience the use of those solutions within their contexts of use.

A symbiont thought of as a socio-technical open system is defined only in terms of the first two ‘cuts’, the third ‘cut’ being implicit in the way its external governance imposes a relationship between the first two. Socio-technical open systems deal with the relational complexity arising from the third ‘cut’ by means of the Faustian Pact its leadership makes with its employees. This says to the employee: perform in terms of the accountability criteria that we have defined normatively for your role, and so long as you meet those criteria, you can do whatever you need to do to satisfy the customer’s expectations, whatever you do remaining your concern alone.

This Faustian Pact is the hallmark of a professional role, a relation that can range from being highly abusive of the individual all the way through to paying huge bonuses to the individual (both extremes leading to burn-out). It is apparent in professional roles such as those of bankers, lawyers, architects, doctors, nurses, salesmen, installers, designers and entrepreneurs. In each case, the critical understanding needed of the particular nature of the customer’s, client’s or patient’s context-of-use is left to the individual. This Faustian Pact extends to the relation between the employees of a Government and its citizens, the effect being that what happens within the citizen’s context-of-use remains the concern of the citizen-individual alone.[5]

Under these Faustian conditions of employment, it is the individual who seeks to be adaptive, in effect building personal equity from what is learnt.[6] The problem created for the corporation (and government) by this Faustian Pact, however, is that it has no way of learning what the employee or subcontractor is learning about the situation of the customer. Not only that, but it also enables leadership to turn a blind eye to the forms of collaborative organization needed to address needs requiring a span-of-complexity greater than that of individuals.[7]

This limitation confronting the external governance of a socio-technical open system becomes apparent with the doubling of the double task[8]. The ‘edge role’ characteristics of a role emerging with this doubling of the double task mean that the role of the corporation too is questioned (Boxer and Eigen 2005). It is the point at which the effects of a current strategy ceiling have to be challenged, i.e., the ceiling above which it is currently none of the individual’s business to question leadership’s sovereignty based on its cybernetic vertical assumptions. The Faustian Pact is thus the necessary means of keeping a strategy ceiling in place (Boxer and Wensley 1996).

The example of the TEF framework

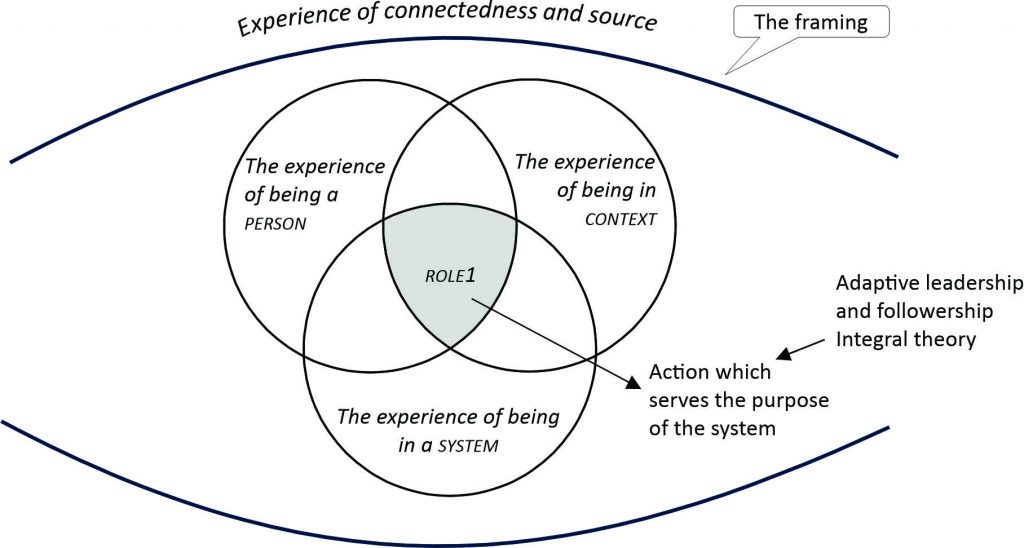

Figure 2 shows the Transforming Experience Framework (TEF) that uses socio-technical open systems thinking (Long 2016). The approach centers on what we are referring to as a normative role, defined as the overlap between the experiences of being a person, being in a system and being in context. The definition of role here is normative because its existence is to serve the purpose of the system as defined by its leadership.[9] To the extent that this purpose is dynamic, the TEF framework approaches this in terms of adaptive leadership and followership that is external to the definition of the role itself:

Figure 2: Adapted from The Transforming Experience Framework (TEF) (Long 2016: figure 1.1, p5)

Figure 2: Adapted from The Transforming Experience Framework (TEF) (Long 2016: figure 1.1, p5)

The experiential/existential framing of the overlapping experience of person, system and context is described by the TEF in terms of the experience of connectedness and source. This framing carries with it an implicit definition of the domain of relevance in relation to which the person-system-context nexus is being experienced. The experience of connectedness derived from this nexus may be approached ‘inside-out’ or ‘outside-in’:

“The TEF framework centres round role because it is within roles that decisions can be made and actions taken. Persons take up roles and act from within their constraints – both explicit and tacit or implicit. However, the traditional egocentric way of seeing persons at the centre of all things can be challenged through the framework. The challenge comes from looking not from the “inside out” (person to group), but from the “outside in” (seeing the group and context first).”(Long 2016: p5)

The definition of the source of this framing is that from which connectedness originates or can be obtained, by means of which energy or a particular component enters a system. In considering the source of this connectedness, the TEF description goes on to say:

“In terms of spiritual source, God, a deity, or even natural forces (e.g., Gaia) may be the source. In more secular terms, source may come from an overall purpose beyond individual egos – a communal purpose or a historical, cultural dynamic.” (Long 2016: p9)

The reference to integral theory in Figure 2 thus adds the ‘individual-collective’ distinction to the ‘inside-outside’ distinction, spanning all four of Ken Wilber’s quadrants[10].

What this TEF framework does is to place the vertical sovereignty of the system as external to the system as experienced by the role, the exercise of that sovereignty being identified with the “adaptive leadership and followership” in Figure 2. This is itself based on an implicit framing of the domain of relevance aka epistemic ‘cut’ in terms of which that sovereignty is exercised. If we want to think of the system as ‘living’, therefore, so that the place of adaptation becomes a general property of the system itself, we need to make all three ‘cuts’ part of how the dynamics of the system itself is understood. This leads to a different understanding of ‘leadership’ as needing to be defined in relation to the desire of the customer rather than in relation to the desire of its leader (Boxer 1998).

Adopting a living system approach

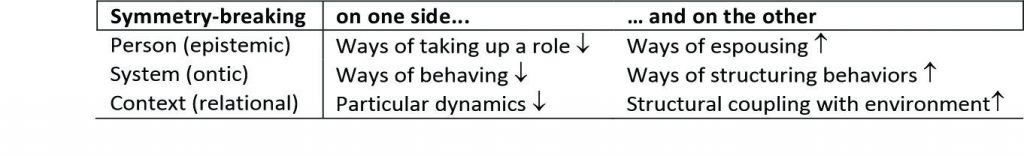

We can think of an organization qua symbiont as a living system by identifying the three circles in Figure 2 with the three ‘cuts’, as show in Figure 3 and Table 1, making the being-in-context a relational ‘cut’ by including its other side. This allows us to make the distinction between the normative role of serving the purpose of the system and the edge role of exercising adaptive leadership and followership, both normative and edge roles being part of how the experience of role is to be understood:

Figure 3: A modified TEF centered on the system per se as a living system

This extends the three-way distinction between person, system and context to add what is on either side of the ‘cut’ in each case[11]:

- Person – the epistemic ‘cut’ between a particular (localized) way of taking up a role and a (non-localized) way of espousing the nature of that role, corresponding to the distinction between a theory-in-use as distinct from an espoused theory.

- System – the ontic ‘cut’ between particular ways of behaving (decoding) and the available ways of structuring the relationships between behaviors (encoding) available to a person, corresponding to the distinction between bottom-up and top-down definitions of behavior.

- Context – the relational ‘cut’ between an organization defined by its own particular dynamics (the thing itself) and the contexts-of-use with which it is structurally coupled, defined by the multiple entities with which it is interacting (relationship to environment). Here the correspondence is with the distinction between the vertical affiliative culture of an organization and the horizontal alliances formed around each customer’s situation as a context-of-use.

Table 1 lists what is on either side of each ‘cut’ using the ‘up’ and ‘down’ arrows. The doubling of the double task is most apparent here in the context ‘cut’: the context in which the normative role is defined is the symbiont as ‘a thing itself’, while the contexts in which the symbiont is taking up its value-creating and value-capturing role is its relationship to its environment.

Table 1: The three ‘cuts’ held in relation to each other by the symbiont

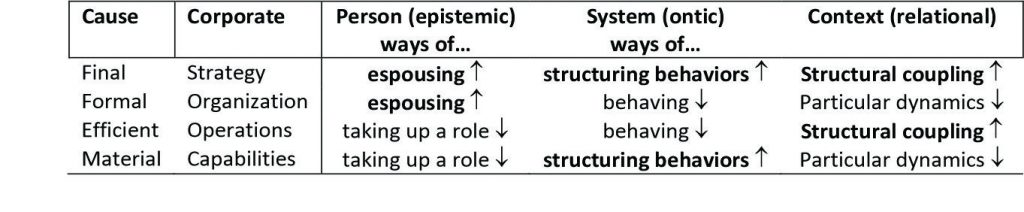

On the basis of these three ‘cuts’, we can relate each of the four causes to ways of describing a symbiont in terms of its capabilities (the material cause), operations (the efficient cause), organization (the formal cause) and strategy (the final cause), strategy here understood as its way of creating value sustainably in its environment[12]. Each cause corresponds to a corner of the quadripod shown in Figure 4, Table 2 showing how the distinctions in Table 1 apply to each of the causes:

On the basis of these three ‘cuts’, we can relate each of the four causes to ways of describing a symbiont in terms of its capabilities (the material cause), operations (the efficient cause), organization (the formal cause) and strategy (the final cause), strategy here understood as its way of creating value sustainably in its environment[12]. Each cause corresponds to a corner of the quadripod shown in Figure 4, Table 2 showing how the distinctions in Table 1 apply to each of the causes:

Table 2: The quadripod for the symbiont

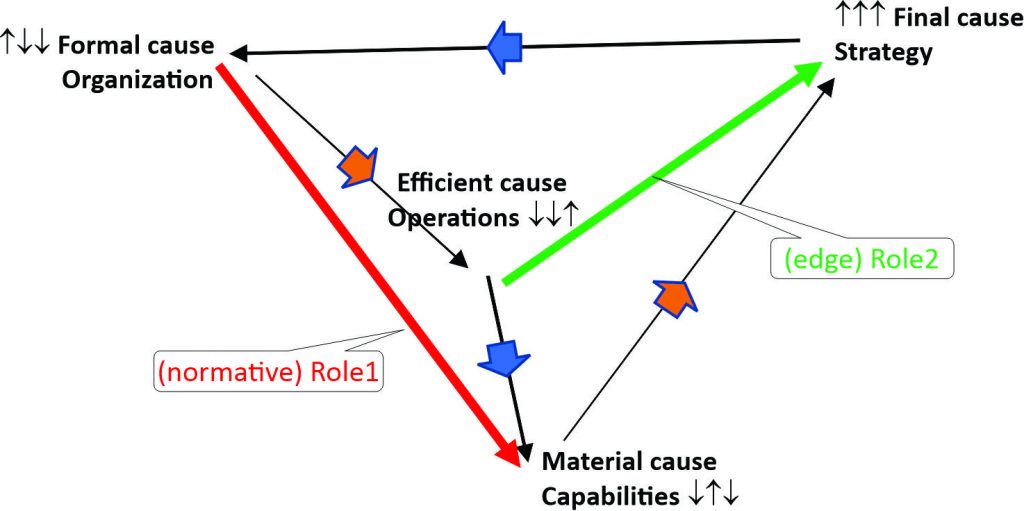

Figure 4 shows the quadripod at the core of Figure 3 without the three ‘cuts’ (hence the ‘up’ and ‘down’ arrows). The red normative Role1 is the relation of formal-cause Organization to material-cause Capabilities, specific to the way the symbiont is defined as a distinct entity. The green Edge Role2 becomes the relation of efficient-cause Operations to final-cause Strategy, specific to the value-creating relation being engendered between the symbiont and its environments. The blue thick arrows between the causes in Figure 4 are the dependency relations on either side of the epistemic ‘cut’ made by the Person and the orange arrows are the dependency relations across this ‘cut’.

Figure 4 shows the quadripod at the core of Figure 3 without the three ‘cuts’ (hence the ‘up’ and ‘down’ arrows). The red normative Role1 is the relation of formal-cause Organization to material-cause Capabilities, specific to the way the symbiont is defined as a distinct entity. The green Edge Role2 becomes the relation of efficient-cause Operations to final-cause Strategy, specific to the value-creating relation being engendered between the symbiont and its environments. The blue thick arrows between the causes in Figure 4 are the dependency relations on either side of the epistemic ‘cut’ made by the Person and the orange arrows are the dependency relations across this ‘cut’.

The direction of the arrows between the causes indicate how they are dependent, following the same logic as in the previous blog. Organization is dependent on both Operations and Capabilities, and Operations are dependent on both Capabilities and Strategy. In contrast, Strategy is dependent only on how the Organization is defined and Capabilities are dependent only on Strategy. The normative Role1 can thus be defined wholly in terms of accountabilities and responsibilities ‘internal’ to the symbiont, while the Edge Role2 must be defined by the way the symbiont anticipates the direct and indirect effects of its behaviors within the environments in which it is seeking to create and capture value:

Figure 4: The quadripod for the symbiont

Figure 4: The quadripod for the symbiont

Here, then, is a way of describing the tension between the normative and edge definitions of a role as a general property of all roles defined by a symbiont that is competing within a turbulent environment. At the level of the individual thinking about their role, the three consistencies of the quadripod become ‘responsibilities’ reflecting an ‘ecosystemic’ consistency holding the epistemic ‘cut’ constant, ‘accountabilities’ reflecting an ‘internalist’ consistency holding the relational ‘cut’ constant, and ‘value-creating relationships’ reflecting the ‘externalist’ consistency holding the ontic ‘cut’ constant.

The doubling of the double task thus involves challenging the way these different consistencies need to be held in relation to each other depending on what kind of relation between value-creation and value-capture is appropriate in any given context-of-use. Whether or not this is possible depends on challenging the cybernetic vertical assumptions currently defining the strategy ceiling[13]. The next blog describes a different approach to understanding the relationship to ‘governance’ in the case of living systems.

Notes

[1] This will involve making a structural distinction between a vertical normative role and an horizontal ‘edge role’ – while the normative role presents the individual with Harold Bridger’s double task of holding the tension between the personal and the normative role (Bridger 1990), the ‘edge role’ doubles this double task in also having to hold the tension between the interests of the organization per se and those of its customers.

[2] The issue of when ‘doing things right’ is not ‘doing the right thing’ is pursued further in the Ethical Dilemmas blog.

[3] Safety II involves minimizing errors of intent (not understanding what is needed aka wrongly diagnosing a problem). In contrast, having been given a diagnosis, Safety I involves avoiding errors of execution (doing things wrong) or errors of planning (combining the wrong things) on the basis of that diagnosis. See (Boxer 2018; Reason 1990; Committee on Quality of Health Care in America 2001)

[4] (i) going beyond 2nd epoch socio-technical open-systems thinking, (ii) what might it mean to ‘surrender sovereignty’ using biological metaphors?, (iii) The three asymmetries necessary to describing agency in living biological systems, and (iv) Triple articulation and the quadripod of a living system.

[5] The limitations inherent to using votes as the only way to influence how a Government uses Corporations, whether public or private, is one of the reasons why democracy falls into disrepute.

[6] By ‘personal equity’ I hear mean know-how accumulated from experience that may or may not be of value to others. For example, in the case of doctors it may lead to improved reputation and potentially higher forms of remuneration, whereas for the nurse, while it may greatly add value in the life of a patient, it is unlikely to lead to higher forms of remuneration for the nurse. This brings us back to the issues that surround the use-value x exchange-value dialectic and how this relation differs on either side of the production x consumption dialectic. See ‘The dialectics implied by the Q-sectors’.

[7] This problem becomes particularly acute in the role of prime contractors delivering complex systems of systems that, in order to be useful when deployed, have to be able to interoperate collaboratively with other systems of systems ‘in the wild’ (Boxer 2012).

[8] This doubling of the double task is not only an issue at large scales but impinges even at the level of the individual, being one of the disruptive effects of social media (Boxer 2013).

[9] Organizational Role Analysis (ORA) (Reed 1976) contrasts the ‘normative’ role (the point of view of what ‘ought’ to be, defined in terms of accountabilities and responsibilities within a system with its roles and boundaries) with the ‘existential’ role (the way a role holder experiences the role itself) and the ‘phenomenological’ role (in which the role is described from the point of view of the proverbial fly-on-the-wall). ORA thus explores how an individual experiences a ‘normative’ role and how that role is ‘performed’ in practice.

[10] The resultant four quadrants of Interior-Individual/Intentional, Exterior-Individual/Behavioral, Interior-Collective/Cultural and Exterior-Collective/Social are defined by Wilber as a comprehensive approach to reality at any level of definition of entity (Wilber 1983). As such it appears based on an implicit relational ‘cut’ that separates out that ‘entity’ with its circular causality, and which is the characteristic of an ‘internalist’ view.

[11] These ways of defining the three ‘cuts’ correspond to the way the dilemmas are described in ‘the dilemmas of ignorance’ (Boxer 1999).

[12] Note here that the way the word ‘strategy’ is being used is not in the commercial sense of achieving a major or overall aim, but in the military sense of achieving the object of war in terms of impacting on ‘the will of the enemy’ (von Clausewitz 1968[1832]: p241). Strategy is thus not defined here in terms of outcomes but in terms of direct and indirect effects within the customer’s context of use. ‘Operations’ is also used here in the military sense to describe the means of achieving particular aims – what is confusingly referred to commercially as strategy!

[13] The presence of a strategy ceiling may also be understood as the basis of counter-resistance to the efforts by edge-role holders to do ‘more’ for the customer. Under these conditions it is the customers and their advocates that are resisting while counter-resistance seeks to conserve existing ways of doing things defined in terms of a cybernetic vertical understanding (Boxer 2017). This counter-resistance, based on the assumptions remaining implicit above the strategy ceiling, form the basis of the way authority is exercised by a corporation’s immune system.

References

Boxer, P J. 2018. “On becoming edge-driven – working with the Double Subjection of Organizations.” In. Working Paper: Boxer Research Ltd.

Boxer, P.J. 1998. ‘The Stratification of Cause: when does the desire of the leader become the leadership of desire?’, Psychanalytische Perspektieven, 32: 137-59.

———. 1999. ‘The dilemmas of ignorance.’ in Chris Oakley (ed.), What is a Group? A fresh look at theory in practice (Rebus Press: London).

———. 2012. The Architecture of Agility: Modeling the relation to Indirect Value within Ecosystems (Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany).

———. 2013. ‘Managing the Risks of Social Disruption: What Can We Learn from the Impact of Social Networking Software?’, Socioanalysis, 15: 32-44.

———. 2014. ‘Leading Organisations Without Boundaries: ‘Quantum’ Organisation and the Work of Making Meaning’, Organizational and Social Dynamics, 14: 130-53.

———. 2017. ‘Working with defences against innovation: the forensic challenge’, Organizational and Social Dynamics, 17: 89-110.

Boxer, P.J., and C.A. Eigen. 2005. “Taking power to the edge of the organisation: re-forming role as praxis.” In Annual Meeting of the ISPSO. Baltimore, Maryland.

Boxer, P.J., and J.R.C. Wensley. 1996. “Performative Organisation: Learning to Design or Designing to Learn.” In, 20. Warwick Business School.

Bridger, H. 1990. ‘Courses and Working Conferences as Transitional Learning Institutions.’ in E. Trist and H. Murray (eds.), The Social Engagement of Social Science (Free Association Books).

Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (National Academy Press).

Long, S. 2016. ‘The Transforming Experience Framework.’ in S. Long (ed.), Transforming Experience in Organisations: A Framework for Organisational Research and Consultancy (Karnac: London).

Reason, James. 1990. Human Error (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK).

Reed, B. 1976. ‘Organisational Role Analysis.’ in C.L. Cooper (ed.), Developing Social Skills in Managers: advances in group training (MacMillan: London).

von Clausewitz, Carl. 1968[1832]. On War (Pelican Books: Harmondsworth, England).

Wilber, Ken. 1983. A Sociable God (McGraw-Hill: New York).

Woodward, Suzette. 2020. Implementing Patient Safety: Addressing Culture, Conditions and Values to Help People Work Safely (Routledge Productivity Press: New York).